Introduction: The Critical Role of Precision in Medical Imaging

In the high-stakes world of modern medicine, a clear picture can mean the difference between life and death. Medical imaging—through modalities like CT, MRI, and ultrasound—provides a non-invasive window into the human body, allowing clinicians to diagnose diseases, plan treatments, and monitor patient progress. However, the sheer volume and complexity of this visual data can be overwhelming. Manually tracing the boundaries of organs, tumors, or blood vessels is a painstaking, time-consuming process prone to human error and inter-observer variability.

This is where the power of artificial intelligence (AI) comes in. Automated medical image segmentation, the process of using AI to pinpoint and outline specific anatomical structures pixel-by-pixel, promises to revolutionize clinical workflows. For years, the field has been dominated by two competing architectural philosophies: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Vision Transformers (ViTs).

- CNNs are masters of local detail, excelling at capturing fine-grained features and textures using small, localized filters.

- ViTs are global context experts, leveraging self-attention mechanisms to understand long-range relationships across an entire image.

But each has a critical weakness: CNNs often miss the “big picture,” while ViTs can overlook crucial local details. What if we could have the best of both worlds? Enter D-Net, a groundbreaking new architecture that dynamically fuses local precision with global understanding, setting a new state-of-the-art for 3D medical image segmentation.

The Architectural Divide: CNNs vs. Transformers in Medicine

To appreciate the innovation of D-Net, it’s essential to understand the limitations of existing technologies.

The CNN Conundrum: Small Windows, Limited View

CNNs, like the famous U-Net, process images using small convolutional kernels (e.g., 3×3). This makes them highly effective for recognizing local patterns like edges and textures, which is vital for identifying organ boundaries. However, their fundamental operation is local. Each neuron only sees a small patch of the input image at a time. To understand a larger context, information must pass through many layers, which can be inefficient and may still fail to capture truly global dependencies. This can lead to anatomical incoherence—for instance, misidentifying a part of the stomach as the pancreas because the model lacks a holistic understanding of their spatial relationship.

The Transformer Trade-off: Global Vision, Local Blindness

Vision Transformers took the AI world by storm by processing images as sequences of patches and using self-attention to model interactions between all patches simultaneously. This gives them an unparalleled ability to incorporate global context. However, this power comes at a steep computational cost, especially for high-resolution 3D medical volumes, where complexity can become prohibitive. Furthermore, the standard practice of “downsampling” images at the input stage to make this computation feasible often discards the very fine-grained, pixel-level information that is critical for precise segmentation. As a result, pure ViTs can struggle with accurately delineating boundaries and segmenting small structures.

Introducing D-Net: A Symphony of Dynamic Modules

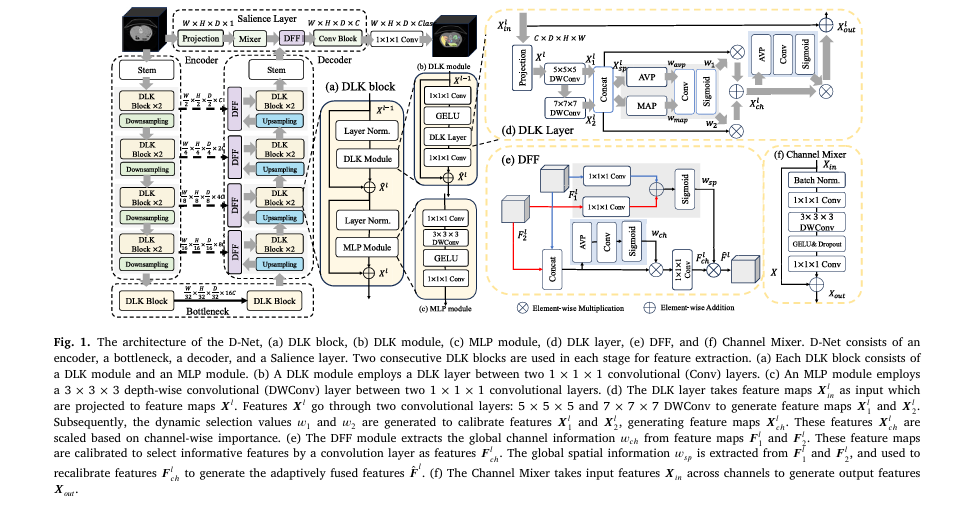

D-Net, proposed by researchers from Washington University in St. Louis and Fudan University, is a novel hierarchical network that ingeniously bridges the gap between CNNs and ViTs. It introduces three core components that work in concert to achieve superior segmentation.

1. The Dynamic Large Kernel (DLK) Module: Smarter, Adaptive Convolutions

Instead of relying on a single, fixed-sized large kernel, the DLK module is a lightweight and intelligent feature extractor.

- Multi-Scale Feature Capture: It employs multiple depth-wise convolutional layers with large, varying kernels and dilation rates. The input features Xinl ∈ RC×H×W×D are first projected to a lower dimension for efficiency:

They are then processed by cascaded depth-wise convolutions:

\[ X_{1}^{l} = \text{DWConv}(5, 1)(X^{l}) \] \[ X_{2}^{l} = \text{DWConv}(7, 3)(X_{1}^{l}) \]By cascading them, the module creates an effective receptive field as large as a 23x23x23 kernel, calculated as:

\[ R_i = R_{i-1} + (k_{i-1}) \ast j_i \]where Ri−1 = 5, ki = 7 + (7−1) ∗ (3−1) = 19, and ji = 1, giving Ri = 5 + (19−1) ∗ 1 = 23. This allows it to capture rich, multi-scale contextual information.

Dynamic Selection Mechanism: This is the “smart” part. The features from the two kernels are concatenated (Xspl = Concat ([ X1l ; X2l ])), and a dynamic mechanism calculates selection weights w1,w2 by analyzing global spatial information through pooling and a convolutional layer:

\[ [w_1; w_2] = \sigma\big(\text{Conv}_7([\,\text{AVP}(X_{\text{spl}});\, \text{MAP}(X_{\text{spl}})\,])\big) \]These weights adaptively calibrate the features: Xchl = ( w1 ⊗ Xspl ) ⊕ (w2 ⊗ Xspl). Finally, a channel-wise attention weight wchwch is applied to highlight the most important channels. In simple terms, it learns to pay more attention to the most informative features and regions based on the global context of the image.

2. The Dynamic Feature Fusion (DFF) Module: Context-Aware Feature Blending

Segmentation networks like U-Net use “skip connections” to fuse high-level, coarse features from the encoder with low-level, fine-grained features from the decoder. D- Net improves this process with its DFF module.

Instead of simply concatenating features, DFF uses a dynamic mechanism to fuse them intelligently. For two feature maps Fil and Fjl, it first concatenates them: Fl = Concat ([ Fil ; Fjl ]). It then uses global information to guide the fusion:

- Channel-wise Selection: It calculates a channel importance vector wchwch to preserve important feature maps:

The features are calibrated and projected:

\[ F_{\text{chl}} = \text{Conv}_1\big(w_{\text{ch}} \otimes F_l\big) \]- Spatial-wise Recalibration: It then extracts global spatial information wspwsp to highlight salient regions in the fused output:

The final output is:

\[ F^{l} = w_{sp} \otimes F_{chl} \]This ensures that the most relevant information from both feature streams is retained and emphasized, leading to more accurate and coherent segmentations, particularly at object boundaries.

3. The Salience Layer: Preserving Precious Low-Level Details

Addressing a key weakness of standard ViTs, D-Net introduces a dedicated Salience Layer that operates directly on the input image at its original resolution, bypassing the early downsampling step.

The core of this layer is a Channel Mixer. For an input XinXin, the Channel Mixer performs the following operations to extract and enhance low-level features:

\[ X = \text{Conv}_{1\times1\times1}(\text{BN}(X_{\text{in}})) \] \[ X = \text{Dropout}\big(\text{GELU}(\text{DWConv}_{3\times3\times3}(X))\big) \] \[ X_{\text{out}} = \text{Dropout}(\text{Conv}_{1\times1\times1}(X)) + X_{\text{in}} \]

This allows D-Net to:

- Extract sharp, low-level features like edges and textures directly from the pixel data.

- Learn global representations even at this early stage, thanks to the Channel Mixer’s design which allows feature interaction across all channels.

- Provide the decoder with pristine, high-detail information that is crucial for producing precise segmentation masks.

Putting D-Net to the Test: Superior Performance Across Diverse Tasks

The researchers rigorously evaluated D-Net on three publicly available and challenging medical image segmentation tasks, demonstrating its remarkable versatility and power.

Table 1: Overview of Segmentation Tasks and D-Net Performance

| Dataset | Modality | Task Description | Key Challenge | D-Net Performance (Mean Dice Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMOS 2022 | CT | Abdominal Multi-Organ Segmentation | Segmenting 15 organs with large shape/size variation | 89.67% |

| MSD Brain Tumor | MRI | Brain Tumor Segmentation | Segmenting heterogeneous tumor sub-regions (ED, ET, NET) | 74.42% |

| MSD Hepatic Vessel | CT | Liver Vessel & Tumor Segmentation | Segmenting thin, tubular vessels and complex tumors | 67.63% |

Key Performance Takeaways:

- Outperformed State-of-the-Art: D-Net achieved the highest Dice scores on all three tasks. The table below shows a detailed comparison on the AMOS dataset, highlighting its consistent superiority across different organ types.

Table 2: Detailed AMOS Multi-Organ Segmentation Performance (Dice Scores)

| Organ | V-Net | nnU-Net | UNETR | Swin UNETR | MedNext | D-Net |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | 95.06 | 96.37 | 90.09 | 95.32 | 95.63 | 97.60 |

| Right Kidney | 93.80 | 95.30 | 91.40 | 94.10 | 94.90 | 96.15 |

| Liver | 96.50 | 97.20 | 95.10 | 96.80 | 96.90 | 97.85 |

| Stomach | 85.20 | 87.90 | 80.50 | 86.10 | 86.50 | 89.45 |

| Pancreas | 72.30 | 76.80 | 65.10 | 74.50 | 75.20 | 79.11 |

| Mean (All 15 Organs) | 84.52 | 87.41 | 74.73 | 85.15 | 86.03 | 89.67 |

- Computational Efficiency: Despite its superior performance, D-Net maintained comparably low computational complexity, as shown in the table below, making it a practical solution for real-world clinical settings.

Table 3: Model Complexity Comparison (Input: 96x96x96)

| Model | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|

| V-Net | 45.66 | 370.52 |

| nnU-Net | 68.38 | 357.13 |

| UNETR | 92.78 | 82.73 |

| Swin UNETR | 62.19 | 329.28 |

| MedNext | 11.65 | 173.05 |

| D-Net | 39.28 | 200.13 |

- Exceptional Generalization: In an external evaluation on a separate spleen dataset, D-Net achieved a zero-shot Dice score of 94.12%, the highest among all models, demonstrating its ability to generalize to unseen data without additional training. The generalization gap ΔDice=DiceInternal−DiceExternalΔDice=DiceInternal−DiceExternal for D-Net was only 3.48, one of the smallest, indicating robust feature learning.

A Deeper Look: What the Ablation Studies Reveal

Ablation studies are crucial for understanding which components of a model contribute to its success. The studies conducted for D-Net provided clear evidence:

- The DLK Module is Key: Replacing the dynamic DLK module with a standard large kernel convolution caused a drop of ~1.5 points in Dice score, proving the value of the adaptive selection mechanism.

- DFF Enhances Fusion: Using simple concatenation instead of the DFF module led to a 1.6-point performance decrease, highlighting the importance of intelligent, dynamic feature fusion.

- The Salience Layer Delivers Detail: Removing the Salience layer resulted in a significant performance drop (from 89.67 to 87.46 Dice), confirming that extracting low-level features at the original resolution is critical for segmentation accuracy.

Table 4: Ablation Study on DLK Module Configurations (AMOS Dataset)

| Backbone | Basic Module | Mean Dice | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv-ViT | 5x5x5 DWConv | 84.37 | 34.88 | 159.79 |

| Conv-ViT | 23x23x23 DWConv | 85.30 | 36.34 | 171.04 |

| Conv-ViT | DLK (Ours) | 86.27 | 38.33 | 173.13 |

| D-Net | 5x5x5 DWConv | 87.62 | 35.83 | 542.58 |

| D-Net | 23x23x23 DWConv | 88.20 | 37.29 | 553.83 |

| D-Net | DLK (Ours) | 89.67 | 39.28 | 555.91 |

The Clinical Impact: Why D-Net Matters for Patients and Doctors

The technical advancements of D-Net translate directly into tangible benefits for healthcare.

- For Radiologists: D-Net can act as a powerful assistant, reducing segmentation time from hours to seconds. This alleviates workload, minimizes fatigue-induced errors, and allows experts to focus on complex diagnostic decisions.

- For Surgeons: Precise segmentation of tumors and critical anatomical structures is vital for pre-surgical planning. D-Net’s accuracy, especially in boundary regions and for small structures, can help in designing better surgical approaches, improving outcomes, and reducing complications.

- For Oncologists: Tracking tumor progression or regression during treatment requires consistent and accurate measurements. D-Net’s robustness ensures reliable longitudinal tracking, enabling more informed treatment adjustments.

- For Medical Research: By providing a highly accurate and generalizable tool, D-Net can accelerate large-scale population studies, drug discovery, and the development of new imaging biomarkers.

Conclusion: The Future of Medical AI is Dynamic and Integrated

D-Net represents a significant leap forward in the quest for a robust, accurate, and efficient medical image segmentation tool. By moving beyond the rigid CNN-vs.-Transformer debate, it introduces a dynamic, integrative philosophy. Its core innovations—the DLK module for adaptive multi-scale context, the DFF module for intelligent fusion, and the Salience layer for preserving low-level detail—create a synergistic system that is greater than the sum of its parts.

The future of medical AI lies in such architectures that are not only powerful but also practical and trustworthy. As models like D-Net continue to evolve and undergo clinical validation, they promise to become indispensable allies in the clinic, enhancing the capabilities of medical professionals and ultimately paving the way for more personalized, precise, and effective patient care.

Engage With Us

What are your thoughts on the future of AI in medical imaging? Do you see dynamic architectures like D-Net becoming the new standard? Share your insights and questions in the comments below—we’d love to start a conversation about the cutting edge of healthcare technology.

To stay updated on the latest breakthroughs in AI and medicine, be sure to subscribe to our newsletter!

Download Paper Here.

Below is the complete python code that implements the D-Net architecture based on the descriptions and diagrams in the paper.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class DLKLayer(nn.Module):

"""

Dynamic Large Kernel (DLK) Layer as described in Section 3.1.1 and Figure 1(d).

This layer cascades two depth-wise convolutions to create a large receptive field

and uses dynamic selection mechanisms for both spatial and channel features.

"""

def __init__(self, in_channels):

super().__init__()

# Project input from C -> C/2

self.projection = nn.Conv3d(in_channels, in_channels // 2, kernel_size=1)

# Cascaded Depth-wise Convolutions

# DWConv (5x5x5, dilation 1). Padding = (5-1)*1 / 2 = 2

self.dwconv1 = nn.Conv3d(

in_channels // 2, in_channels // 2,

kernel_size=5, padding=2, dilation=1, groups=in_channels // 2

)

# DWConv (7x7x7, dilation 3). Padding = (7-1)*3 / 2 = 9

self.dwconv2 = nn.Conv3d(

in_channels // 2, in_channels // 2,

kernel_size=7, padding=9, dilation=3, groups=in_channels // 2

)

# Spatial Dynamic Selection

# Input to this conv is 2 channels (avg_pool, max_pool)

# Output is 2 channels (w1, w2)

# Kernel 7x7x7. Padding = (7-1)*1 / 2 = 3

self.spatial_mixer_conv = nn.Conv3d(2, 2, kernel_size=7, padding=3)

# Channel Dynamic Selection

self.channel_mixer_pool = nn.AdaptiveAvgPool3d(1)

# 1x1x1 Conv

self.channel_mixer_conv = nn.Conv3d(in_channels, in_channels, kernel_size=1)

self.sigmoid = nn.Sigmoid()

def forward(self, x):

# Store original input for residual connection

x_in = x

# Project C -> C/2

x_proj = self.projection(x)

# Cascaded DWConvs

x1 = self.dwconv1(x_proj)

x2 = self.dwconv2(x1) # Applied sequentially

# Concatenate features from two LKs: C/2 + C/2 -> C

x_sp = torch.cat([x1, x2], dim=1)

# Spatial Dynamic Selection

# Get channel-wise average and max

w_avp = torch.mean(x_sp, dim=1, keepdim=True)

w_map = torch.max(x_sp, dim=1, keepdim=True)[0]

# Concat avg and max pools (B, 2, H, W, D)

w_mix = torch.cat([w_avp, w_map], dim=1)

# Get dynamic selection values w1, w2

w1, w2 = torch.chunk(self.sigmoid(self.spatial_mixer_conv(w_mix)), 2, dim=1)

# Calibrate features

x_ch = (w1 * x_sp) + (w2 * x_sp)

# Channel Dynamic Selection

# Get channel-wise importance

w_ch = self.sigmoid(self.channel_mixer_conv(self.channel_mixer_pool(x_ch)))

# Scale features and add residual connection (from original input x_in)

out = w_ch * x_ch + x_in

return out

class MLPModule(nn.Module):

"""

MLP Module as described in Figure 1(c).

Uses a 3x3x3 Depth-wise Conv.

"""

def __init__(self, in_channels, mlp_ratio=4):

super().__init__()

hidden_channels = in_channels * mlp_ratio

# 1x1x1 Conv to expand channels

self.conv1 = nn.Conv3d(in_channels, hidden_channels, kernel_size=1)

# 3x3x3 DWConv

self.dwconv = nn.Conv3d(

hidden_channels, hidden_channels,

kernel_size=3, padding=1, groups=hidden_channels

)

self.gelu = nn.GELU()

# 1x1x1 Conv to compress channels

self.conv2 = nn.Conv3d(hidden_channels, in_channels, kernel_size=1)

def forward(self, x):

x = self.conv1(x)

x = self.dwconv(x)

x = self.gelu(x)

x = self.conv2(x)

return x

class DLKModule(nn.Module):

"""

DLK Module as described in Section 3.1.2 and Figure 1(b).

This module wraps the DLKLayer with 1x1 convs and a residual connection.

"""

def __init__(self, dim):

super().__init__()

self.conv1 = nn.Conv3d(dim, dim, kernel_size=1)

self.gelu = nn.GELU()

self.dlk_layer = DLKLayer(dim)

self.conv2 = nn.Conv3d(dim, dim, kernel_size=1)

def forward(self, x):

x_in = x

x = self.conv1(x)

x = self.gelu(x)

x = self.dlk_layer(x)

x = self.conv2(x)

out = x + x_in # Residual connection

return out

class DLKBlock(nn.Module):

"""

DLK Block as described in Section 3.1.3 and Figure 1(a).

This is the standard ViT block structure, replacing Multi-Head Self-Attention

with the DLKModule.

"""

def __init__(self, dim, mlp_ratio=4):

super().__init__()

# Per the paper, Layer Normalization is applied.

# For channels-first data (B, C, H, W, D), GroupNorm(1, C) is

# equivalent to LayerNorm.

self.norm1 = nn.GroupNorm(num_groups=1, num_channels=dim)

self.dlk_module = DLKModule(dim)

self.norm2 = nn.GroupNorm(num_groups=1, num_channels=dim)

self.mlp_module = MLPModule(in_channels=dim, mlp_ratio=mlp_ratio)

def forward(self, x):

# Residual connection 1

x = x + self.dlk_module(self.norm1(x))

# Residual connection 2

x = x + self.mlp_module(self.norm2(x))

return x

class DFFModule(nn.Module):

"""

Dynamic Feature Fusion (DFF) Module as described in Section 3.2 and Figure 1(e).

Fuses features from encoder (f1) and decoder (f2).

"""

def __init__(self, in_channels):

super().__init__()

# Global channel information

self.pool = nn.AdaptiveAvgPool3d(1)

self.channel_attn_conv = nn.Conv3d(in_channels * 2, in_channels * 2, kernel_size=1)

self.sigmoid = nn.Sigmoid()

# Channel reduction

self.channel_reduce_conv = nn.Conv3d(in_channels * 2, in_channels, kernel_size=1)

# Global spatial information

self.spatial_attn_conv1 = nn.Conv3d(in_channels, in_channels, kernel_size=1)

self.spatial_attn_conv2 = nn.Conv3d(in_channels, in_channels, kernel_size=1)

def forward(self, f1, f2):

# f1: from encoder (skip connection)

# f2: from decoder (upsampled)

# Concatenate along channel dim

f = torch.cat([f1, f2], dim=1) # (B, 2C, H, W, D)

# Channel-wise selection

w_ch = self.sigmoid(self.channel_attn_conv(self.pool(f)))

f_ch = self.channel_reduce_conv(w_ch * f) # (B, C, H, W, D)

# Spatial-wise selection

w_sp = self.sigmoid(self.spatial_attn_conv1(f1) + self.spatial_attn_conv2(f2))

# Calibrate features

out = w_sp * f_ch

return out

class ChannelMixer(nn.Module):

"""

Channel Mixer as described in Section 3.3.2 and Figure 1(f).

Used within the Salience Layer.

"""

def __init__(self, dim, expansion_ratio=4, dropout=0.1):

super().__init__()

hidden_dim = dim * expansion_ratio

self.norm = nn.BatchNorm3d(dim)

# 1x1x1 Conv to expand channels

self.conv1 = nn.Conv3d(dim, hidden_dim, kernel_size=1)

# 3x3x3 DWConv

self.dwconv = nn.Conv3d(

hidden_dim, hidden_dim,

kernel_size=3, padding=1, groups=hidden_dim

)

self.gelu = nn.GELU()

self.dropout1 = nn.Dropout(dropout)

# 1x1x1 Conv to compress channels

self.conv2 = nn.Conv3d(hidden_dim, dim, kernel_size=1)

self.dropout2 = nn.Dropout(dropout)

def forward(self, x):

x_in = x # Store for residual connection

x = self.norm(x)

x = self.conv1(x)

x = self.dwconv(x)

x = self.gelu(x)

x = self.dropout1(x)

x = self.conv2(x)

x = self.dropout2(x)

out = x + x_in # Residual connection

return out

class SalienceLayer(nn.Module):

"""

Salience Layer as described in Section 3.3.1 and Figure 1.

Extracts low-level features from the original image and fuses them

with the final decoder output.

"""

def __init__(self, dim):

super().__init__()

# Project input image (1 channel) to C channels

self.projection = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv3d(1, dim, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm3d(dim),

nn.LeakyReLU(inplace=True)

)

# Channel Mixer

self.mixer = ChannelMixer(dim)

# DFF to fuse with decoder features

self.dff = DFFModule(dim)

# Convolution block to refine features

self.conv_block = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv3d(dim, dim, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm3d(dim),

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv3d(dim, dim, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm3d(dim),

nn.ReLU(inplace=True)

)

def forward(self, x_image, x_decoder):

# x_image: original input image (B, 1, H, W, D)

# x_decoder: output from final decoder stem (B, C, H, W, D)

# Extract low-level features from image

x_low_level = self.projection(x_image)

x_low_level = self.mixer(x_low_level)

# Fuse low-level features with high-level decoder features

x_fused = self.dff(x_low_level, x_decoder)

# Refine fused features

out = self.conv_block(x_fused)

return out

class Downsampling(nn.Module):

"""

Downsampling block (Conv 3x3x3, stride 2)

"""

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels):

super().__init__()

self.conv = nn.Conv3d(

in_channels, out_channels,

kernel_size=3, stride=2, padding=1

)

def forward(self, x):

return self.conv(x)

class Upsampling(nn.Module):

"""

Upsampling block (ConvTranspose 2x2x2, stride 2)

"""

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels):

super().__init__()

self.conv_t = nn.ConvTranspose3d(

in_channels, out_channels,

kernel_size=2, stride=2

)

def forward(self, x):

return self.conv_t(x)

class DNet(nn.Module):

"""

The complete D-Net architecture as described in Section 3.4 and Figure 1.

"""

def __init__(self, in_chans=1, num_classes=3, base_dim=48, depths=[2, 2, 2, 2], mlp_ratio=4):

super().__init__()

self.num_classes = num_classes

dims = [base_dim * (2**i) for i in range(len(depths) + 1)] # [C, 2C, 4C, 8C, 16C]

# === Encoder ===

# Stem: 7x7x7 Conv, stride 2

self.stem = nn.Conv3d(

in_chans, dims[0],

kernel_size=7, stride=2, padding=3

)

# Stage 1

self.enc_stage1 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[0], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[0])]

)

self.down1 = Downsampling(dims[0], dims[1])

# Stage 2

self.enc_stage2 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[1], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[1])]

)

self.down2 = Downsampling(dims[1], dims[2])

# Stage 3

self.enc_stage3 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[2], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[2])]

)

self.down3 = Downsampling(dims[2], dims[3])

# Stage 4

self.enc_stage4 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[3], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[3])]

)

self.down4 = Downsampling(dims[3], dims[4])

# === Bottleneck ===

self.bottleneck = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[4], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[3])] # Paper uses 2 blocks

)

# === Decoder ===

# Stage 1 (from 16C -> 8C)

self.up1 = Upsampling(dims[4], dims[3])

self.dff1 = DFFModule(dims[3])

self.dec_stage1 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[3], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[3])]

)

# Stage 2 (from 8C -> 4C)

self.up2 = Upsampling(dims[3], dims[2])

self.dff2 = DFFModule(dims[2])

self.dec_stage2 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[2], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[2])]

)

# Stage 3 (from 4C -> 2C)

self.up3 = Upsampling(dims[2], dims[1])

self.dff3 = DFFModule(dims[1])

self.dec_stage3 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[1], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[1])]

)

# Stage 4 (from 2C -> C)

self.up4 = Upsampling(dims[1], dims[0])

self.dff4 = DFFModule(dims[0])

self.dec_stage4 = nn.Sequential(

*[DLKBlock(dims[0], mlp_ratio) for _ in range(depths[0])]

)

# Decoder Stem (from C -> C, upsample to full res)

self.decoder_stem = Upsampling(dims[0], dims[0])

# === Salience Layer ===

self.salience = SalienceLayer(dims[0])

# === Final Output ===

self.out_conv = nn.Conv3d(dims[0], num_classes, kernel_size=1)

def forward(self, x):

# x: (B, 1, H, W, D)

x_image = x

# Encoder

s1 = self.enc_stage1(self.stem(x)) # (B, C, H/2, W/2, D/2)

s2 = self.enc_stage2(self.down1(s1)) # (B, 2C, H/4, W/4, D/4)

s3 = self.enc_stage3(self.down2(s2)) # (B, 4C, H/8, W/8, D/8)

s4 = self.enc_stage4(self.down3(s3)) # (B, 8C, H/16, W/16, D/16)

# Bottleneck

b = self.bottleneck(self.down4(s4)) # (B, 16C, H/32, W/32, D/32)

# Decoder

d1 = self.dec_stage1(self.dff1(s4, self.up1(b))) # (B, 8C, H/16, W/16, D/16)

d2 = self.dec_stage2(self.dff2(s3, self.up2(d1))) # (B, 4C, H/8, W/8, D/8)

d3 = self.dec_stage3(self.dff3(s2, self.up3(d2))) # (B, 2C, H/4, W/4, D/4)

d4 = self.dec_stage4(self.dff4(s1, self.up4(d3))) # (B, C, H/2, W/2, D/2)

# Decoder Stem

x_decoder = self.decoder_stem(d4) # (B, C, H, W, D)

# Salience Layer

x_salience = self.salience(x_image, x_decoder) # (B, C, H, W, D)

# Final Output

out = self.out_conv(x_salience) # (B, num_classes, H, W, D)

# Apply sigmoid or softmax for probabilities if needed (often done in loss function)

# For multi-label (e.g., AMOS), use sigmoid

# For multi-class (e.g., BraTS), use softmax

return out

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Test the D-Net model with a dummy input

# Parameters from the paper

BASE_DIM = 48

NUM_CLASSES = 15 # For AMOS dataset

INPUT_CHANS = 1 # For CT/MRI

# Let's test with a common patch size mentioned (e.g., 128x128x128)

# The model is fully convolutional, so it can handle different sizes,

# but patch size must be divisible by 2^5 (32)

# Using 96x96x96 as a test case (divisible by 32)

D, H, W = 96, 96, 96

# Create a dummy input tensor

# (Batch_size, in_channels, Depth, Height, Width)

dummy_input = torch.randn(1, INPUT_CHANS, D, H, W)

print(f"Input shape: {dummy_input.shape}")

# Instantiate the model

# Depths [2, 2, 2, 2] as per Figure 1 (2 DLK blocks per stage)

model = DNet(

in_chans=INPUT_CHANS,

num_classes=NUM_CLASSES,

base_dim=BASE_DIM,

depths=[2, 2, 2, 2]

)

print(f"Model instantiated. Base dimension: {BASE_DIM}")

# Perform a forward pass

try:

with torch.no_grad():

output = model(dummy_input)

print(f"Output shape: {output.shape}")

# Check if output shape matches input spatial dimensions and num_classes

assert output.shape == (1, NUM_CLASSES, D, H, W)

print("\nModel forward pass successful!")

# Optional: Print parameter count

total_params = sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters() if p.requires_grad)

print(f"Total trainable parameters: {total_params / 1_000_000:.2f} M")

except Exception as e:

print(f"\nAn error occurred during the model test: {e}")

import traceback

traceback.print_exc()

Related posts, You May like to read

- 7 Shocking Truths About Knowledge Distillation: The Good, The Bad, and The Breakthrough (SAKD)

- 7 Revolutionary Breakthroughs in Medical Image Translation (And 1 Fatal Flaw That Could Derail Your AI Model)

- TimeDistill: Revolutionizing Time Series Forecasting with Cross-Architecture Knowledge Distillation

- HiPerformer: A New Benchmark in Medical Image Segmentation with Modular Hierarchical Fusion

- GeoSAM2 3D Part Segmentation — Prompt-Controllable, Geometry-Aware Masks for Precision 3D Editing

- Probabilistic Smooth Attention for Deep Multiple Instance Learning in Medical Imaging

- A Knowledge Distillation-Based Approach to Enhance Transparency of Classifier Models

- Towards Trustworthy Breast Tumor Segmentation in Ultrasound Using AI Uncertainty

- Discrete Migratory Bird Optimizer with Deep Transfer Learning for Multi-Retinal Disease Detection

Solid points all around.