Introduction: The Critical Need for Accurate Medical Image Segmentation

In the high-stakes world of modern radiology, the precise delineation of organs and tumors within CT and MRI scans is not merely a technical exercise—it’s a cornerstone of patient care. This process, known as medical image segmentation, is vital for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment planning, and ongoing disease monitoring. A surgeon relies on these segmented images to navigate delicate tissue during an operation; an oncologist uses them to calculate radiation doses that maximize tumor destruction while sparing healthy organs. Yet, for decades, this critical task has been performed manually by skilled radiologists, a process that is both labor-intensive and time-consuming, creating bottlenecks in patient care.

The advent of deep learning promised to automate this process, offering the potential for faster, more consistent, and scalable analysis. However, most existing AI models have fallen short of their promise. They are typically highly specialized, trained on specific datasets for particular organ systems or imaging modalities. This lack of generalizability means a model trained to segment the liver on a CT scan often fails miserably when asked to segment the pancreas on an MRI, forcing institutions to develop and maintain a separate, costly model for each clinical need. The dream of a single, universal AI tool for medical imaging has remained elusive.

Enter Vision Foundation Models (FMs). These are large-scale neural networks pretrained on billions of natural images from the web. Models like DINOv2 and DINOv3 have demonstrated remarkable success in computer vision, producing powerful, transferable representations that can be adapted to a wide array of downstream tasks—from object detection to semantic segmentation—without requiring massive amounts of new labeled data. The question, then, is compelling: Can these powerful models, trained on cats and cars, be effectively transferred to the domain of human anatomy? The answer, as revealed by the groundbreaking research behind MedDINOv3, is a resounding yes—with the right adaptations. This article will delve into how MedDINOv3 overcomes the key challenges of adapting foundation models for medical use, achieving state-of-the-art results and paving the way for a new era of unified, generalizable AI in radiology.

The Two Major Hurdles: Architecture and Domain Gap

Before we explore the solution, it’s crucial to understand the two fundamental challenges that have prevented the direct application of vision foundation models to medical imaging.

1. The Architectural Mismatch: ViTs vs. CNNs

Most leading vision foundation models are built upon the Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture. While ViTs excel at global reasoning and scaling to massive datasets, they have historically lagged behind Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in dense prediction tasks like segmentation. CNNs possess a strong inherent “locality bias”—they are naturally designed to understand spatial relationships between neighboring pixels, which is essential for accurately outlining the boundaries of an organ or tumor. ViTs, in contrast, treat an image as a sequence of patches and rely on self-attention mechanisms to learn relationships, which can struggle with fine-grained, local details unless specifically engineered for it. Existing medical segmentation models based on ViTs often resort to complex, hybrid architectures that incorporate heavy convolutional components, undermining the simplicity and scalability of the pure transformer approach.

2. The Domain Gap: Natural Images vs. Medical Scans

The second, and perhaps more significant, challenge is the vast domain gap. Foundation models are pretrained on datasets filled with everyday objects, landscapes, and people. Medical images, however, present a completely different visual language. They are grayscale, exhibit unique textures and contrasts, and contain anatomical structures that bear no resemblance to anything in the natural world. Features learned from millions of cat photos are simply not directly applicable to identifying a kidney tumor. This mismatch severely limits the transferability of pre-trained weights, often requiring extensive, expensive retraining on large, curated medical datasets—a luxury not always available due to privacy constraints and data scarcity.

Introducing MedDINOv3: A Simple, Effective Framework for Adaptation

MedDINOv3 is not just another complex model; it is a carefully designed framework for adapting the powerful DINOv3 foundation model to the specific demands of medical image segmentation. Its brilliance lies in its simplicity and its targeted approach to solving the two core problems identified above. Rather than building a monolithic, bespoke architecture, MedDINOv3 starts with a proven foundation—the DINOv3 ViT encoder—and introduces two key, elegant refinements to make it suitable for dense medical tasks.

Refinement 1: Multi-Scale Token Aggregation for Richer Spatial Context

The first refinement tackles the architectural weakness of plain ViTs. In standard ViT-based segmentation, the decoder typically receives only the final output from the last transformer block. This single, aggregated representation lacks the hierarchical, multi-scale information that CNNs leverage so effectively. To address this, MedDINOv3 implements multi-scale token aggregation.

Instead of discarding the intermediate outputs, the framework reuses patch tokens from several intermediate layers of the transformer encoder—specifically blocks 2, 5, 8, and 11. These tokens, representing features at different levels of abstraction, are concatenated and fed together into the lightweight decoder. This provides the decoder with a much richer, more detailed view of the image, incorporating both coarse global context and fine local detail. It essentially injects the missing “spatial priors” into the ViT, mitigating its weak locality bias and allowing it to better understand the intricate shapes and boundaries of anatomical structures.

Refinement 2: High-Resolution Training to Preserve Local Detail

The second refinement addresses the need to capture fine-grained detail. Previous work, such as Primus, suggested reducing the patch size during tokenization (from 16×16 to 8×8 pixels) to preserve more local information. However, this approach is computationally expensive and incompatible with many pre-trained foundation models, which are optimized for larger patch sizes.

MedDINOv3 offers a more practical and effective solution: high-resolution training. Instead of changing the patch size, the researchers simply train the model on input images that have been resampled to a higher resolution. For their experiments, they used an input resolution of 896×896 pixels, significantly larger than the 640×640 resolution used in baseline comparisons. This allows the model to see more pixel-level detail without altering the fundamental architecture of the pre-trained ViT backbone. The result is a model that can produce smoother, more accurate segmentation maps, particularly around the complex boundaries of organs and tumors.

These two refinements, when combined, create a simple yet potent architecture. An ablation study on the AMOS22 dataset clearly demonstrates their impact:

- Starting with a randomly initialized ViT-B encoder and a Primus decoder: 78.39% DSC.

- Adding a DINOv3-pretrained encoder: +2.96% to 81.35% DSC.

- Adding multi-scale token aggregation: +2.10% to 83.45% DSC.

- Adding high-resolution training (896×896): +2.06% to 85.51% DSC.

This step-by-step improvement highlights how each component contributes to closing the performance gap with CNNs.

Domain-Adaptive Pretraining: Aligning the Model with Medical Reality

A powerful architecture is only half the battle. To truly bridge the domain gap, MedDINOv3 employs a sophisticated, three-stage domain-adaptive pretraining process on a massive, curated medical dataset called CT-3M.

Data Curation: Building CT-3M

The foundation of this pretraining is CT-3M, a colossal collection of 3,868,833 axial CT slices. This dataset was meticulously curated by aggregating data from 16 diverse, publicly available sources, including BTCV, KiTS, LiTS, AMOS22, and the Medical Segmentation Decathlon. This ensures broad anatomical coverage (over 100 distinct structures) across abdominal, thoracic, and pelvic regions, providing the model with the scale and heterogeneity needed to learn robust, generalizable features. All volumes were standardized to a uniform in-plane spacing of 0.45 mm and resized to 256×256 pixels for consistency.

The Three-Stage Pretraining Recipe

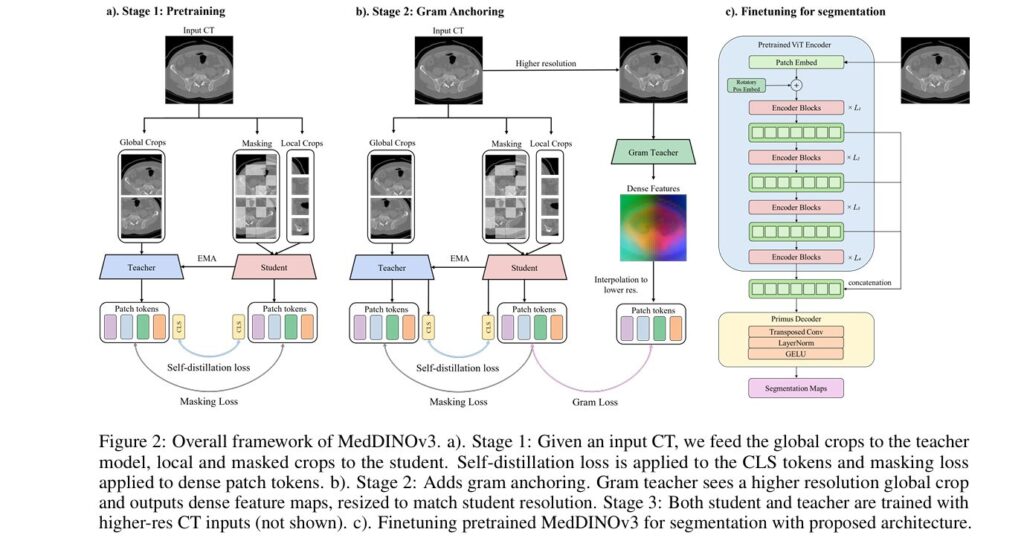

The pretraining follows the advanced DINOv3 recipe, adapted for medical data:

- Stage 1: Global/Local Self-Distillation (DINOv2-style) This stage uses the core DINOv2 losses to teach the model to produce consistent representations for different views of the same image. It includes:

- The total loss for Stage 1 is defined as:

This stage is run for 100k iterations and serves as the primary driver for learning good, dense features from the medical domain.

- Stage 2: Gram Anchoring (Optional Stabilizer) In DINOv2 training, it was observed that global objectives can dominate, leading to a slow degradation of patch-level feature quality. Stage 2 introduces gram anchoring to mitigate this. A “Gram teacher” model, taken from an early checkpoint of the pretraining, generates dense feature maps from higher-resolution inputs (512×512). The student model is then encouraged to align its own Gram matrix (the matrix of all pairwise dot products of its patch features) with that of the Gram teacher. The Gram anchoring loss is defined as:

where XS and XG are the normalized feature matrices of the student and Gram teacher, respectively. Surprisingly, the MedDINOv3 authors found this stage provided only marginal gains, suggesting that the initial DINOv2-style pretraining was already sufficient for maintaining patch-level quality on their medical data.

- Stage 3: High-Resolution Adaptation The final stage adapts the model to process even higher-resolution images, which is critical for medical tasks. The model is trained using a mix of global and local crops at various resolutions (e.g., global crops 512–768, local crops 112–336). Crucially, gram anchoring is retained in this stage to ensure the stability of the patch similarity structures learned previously. This stage lasts for 10k iterations and significantly improves the model’s ability to generate high-fidelity, dense features at the resolutions required for clinical use.

State-of-the-Art Results: Outperforming the Gold Standard

The true test of any medical AI model is its performance on real-world benchmarks. MedDINOv3 was evaluated on four diverse public datasets covering both Organ-at-Risk (OAR) and tumor segmentation tasks across CT and MRI modalities.

| METHOD | AMOS22 (OAR) | KITS23 (TUMOR) | LITS (TUMOR) | BTCV (OAR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nnU-Net | 84.81 | 69.15 | 75.00 | 73.30 |

| SegFormer | 78.50 | 57.73 | 65.45 | 37.04 |

| Dino U-Net | 80.90 | 59.77 | 72.89 | 66.88 |

| MedDINOv3 | 87.38 | 70.68 | 75.28 | 78.79 |

The results are unequivocal. MedDINOv3 consistently outperforms the long-standing gold standard, nnU-Net, in OAR segmentation tasks, achieving a remarkable +2.57% DSC on AMOS22 and a staggering +5.49% DSC on BTCV. On tumor segmentation tasks (KiTS23 and LiTS), MedDINOv3 performs on par with or slightly better than nnU-Net, demonstrating its versatility across different types of segmentation challenges. The results also show that simpler transformer models like SegFormer, designed for natural images, underperform significantly, highlighting the necessity of domain-specific adaptation. Even other DINOv3-based approaches like Dino U-Net, which rely on hierarchical CNN decoders, fail to surpass nnU-Net, underscoring the importance of MedDINOv3’s unique architectural refinements.

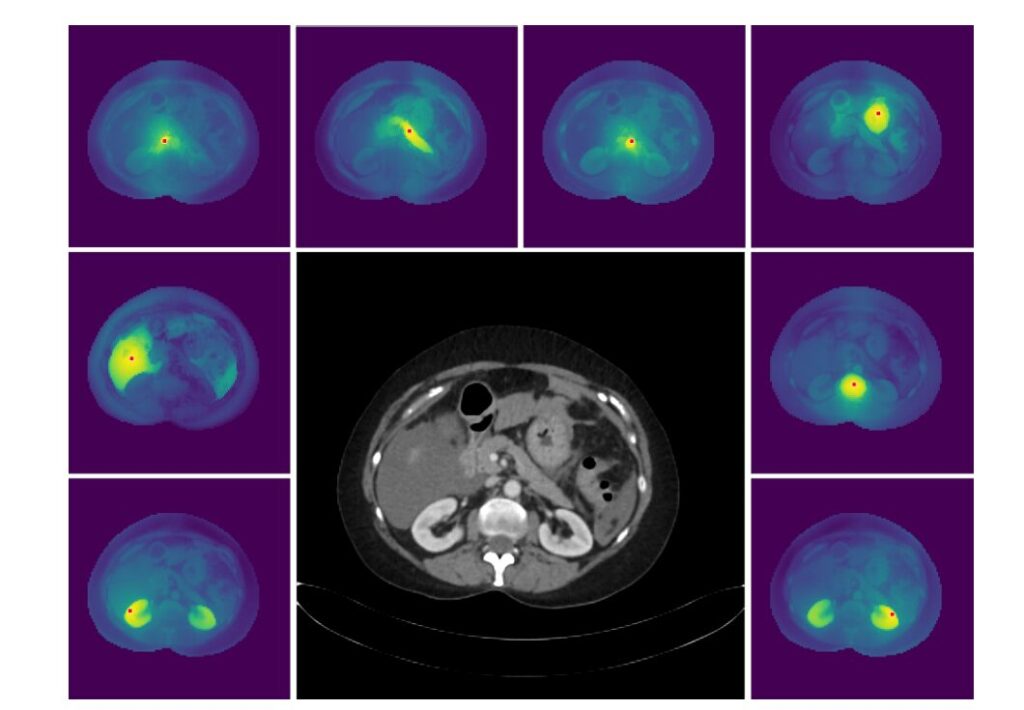

Image Description: Figure 3 – High-Resolution Dense Features of MedDINOv3.

- Alt Text: “Visualization of MedDINOv3’s cosine similarity map on a 2048×2048 CT scan. A red dot marks a reference patch, and the map shows its similarity to all other patches, demonstrating the model’s ability to capture fine-grained, high-resolution anatomical details.”

Conclusion: A Unified Backbone for the Future of Radiology

MedDINOv3 represents a significant leap forward in medical AI. It successfully demonstrates that vision foundation models, far from being irrelevant to medicine, can be adapted to become powerful, generalizable backbones for medical image segmentation. The key to its success lies not in complexity, but in thoughtful, targeted design.

By revisiting the plain ViT architecture and introducing two simple yet effective refinements—multi-scale token aggregation and high-resolution training—MedDINOv3 overcomes the inherent weaknesses of transformers for dense prediction. By performing domain-adaptive pretraining on the massive CT-3M dataset using a systematic, three-stage recipe, it bridges the formidable gap between natural and medical images.

The results speak for themselves: MedDINOv3 matches or exceeds the performance of the dominant nnU-Net baseline, setting a new state-of-the-art for OAR segmentation. This achievement validates the potential of foundation models to serve as a unified, adaptable platform for a wide range of medical imaging tasks, moving us closer to a future where one powerful AI can handle diverse clinical needs, reducing development costs and accelerating innovation.

Call to Action:

The future of radiology is intelligent, automated, and unified. If you’re a researcher, clinician, or developer interested in pushing the boundaries of medical AI, explore the MedDINOv3 codebase on GitHub. The open-source nature of this project invites collaboration, experimentation, and further innovation. We encourage you to download the code, replicate the results, and contribute your ideas to make this powerful framework even more robust and accessible. How do you envision applying MedDINOv3 in your own work? Share your thoughts and questions in the comments below—we’re eager to hear from you and build the next generation of medical AI together.

Downloas and Read the Full paper Here.

Here is the complete code that described in the paper (Figure 2c).

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

import timm

from typing import List

class DecoderBlock(nn.Module):

"""

A single block for the lightweight decoder.

Upsamples by 2x using ConvTranspose2d, followed by normalization and activation.

As per the paper: "transposed convolution, LayerNorm, and GELU".

We use GroupNorm as a more standard normalization layer in CNN-style blocks.

"""

def __init__(self, in_channels: int, out_channels: int):

super().__init__()

# Using kernel_size=2 and stride=2 doubles the spatial resolution

self.conv_transpose = nn.ConvTranspose2d(

in_channels,

out_channels,

kernel_size=2,

stride=2

)

# Using GroupNorm(32, ...) is a common and robust practice.

# If out_channels is not divisible by 32, we use a smaller group count.

num_groups = 32 if out_channels % 32 == 0 else (16 if out_channels % 16 == 0 else 8)

if out_channels < num_groups:

num_groups = 1 # Equivalent to LayerNorm on channels

self.norm = nn.GroupNorm(num_groups, out_channels)

self.activation = nn.GELU()

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

x = self.conv_transpose(x)

x = self.norm(x)

x = self.activation(x)

return x

class PrimusDecoder(nn.Module):

"""

The "Primus decoder" described in the paper.

It's a lightweight decoder that takes concatenated patch tokens and upsamples them

to the full original resolution.

A patch size of 16 means we need to upsample by 16x.

Since 16 = 2^4, we will use 4 DecoderBlocks stacked together.

"""

def __init__(self, in_channels: int, num_classes: int, decoder_width: int = 768):

super().__init__()

# First layer reduces the concatenated channels

self.input_conv = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, decoder_width, kernel_size=1)

# 4 blocks to upsample 16x (2x * 2x * 2x * 2x)

self.block1 = DecoderBlock(decoder_width, decoder_width // 2)

self.block2 = DecoderBlock(decoder_width // 2, decoder_width // 4)

self.block3 = DecoderBlock(decoder_width // 4, decoder_width // 8)

self.block4 = DecoderBlock(decoder_width // 8, decoder_width // 16)

# Final 1x1 convolution to map to the number of segmentation classes

self.output_conv = nn.Conv2d(decoder_width // 16, num_classes, kernel_size=1)

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

x = self.input_conv(x)

x = self.block1(x)

x = self.block2(x)

x = self.block3(x)

x = self.block4(x)

x = self.output_conv(x)

return x

class MedDINOv3_Segmentor(nn.Module):

"""

The main MedDINOv3 segmentation model architecture (Figure 2c).

This model:

1. Uses a pretrained ViT encoder (DINOv3 in paper, we use DINOv2 here).

2. Extracts multi-scale patch tokens from intermediate blocks.

3. Concatenates these tokens.

4. Passes them to the lightweight PrimusDecoder for upsampling.

"""

def __init__(self, num_classes: int, patch_size: int = 16):

super().__init__()

self.num_classes = num_classes

self.patch_size = patch_size

# --- Encoder ---

# The paper uses ViT-B (Base) and DINOv3 weights.

# We use a DINOv2-pretrained ViT-B from timm as the closest public equivalent.

# 'features_only=True' makes it output features instead of a class token.

# 'out_indices' specifies which blocks to get output from.

# The paper uses blocks 2, 5, 8, and 11 (0-indexed).

self.encoder = timm.create_model(

'vit_base_patch16_224.dinov2', # DINOv2 weights

pretrained=True,

features_only=True,

out_indices=[2, 5, 8, 11]

)

# Get the embedding dimension (e.g., 768 for ViT-B)

self.embed_dim = self.encoder.feature_info.info[-1]['num_ftrs']

# We are concatenating features from 4 blocks

decoder_in_channels = self.embed_dim * 4

# --- Decoder ---

self.decoder = PrimusDecoder(

in_channels=decoder_in_channels,

num_classes=num_classes

)

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

# Get input spatial dimensions

B, _, H, W = x.shape

# Calculate the patch grid dimensions

# E.g., 896x896 input -> 56x56 patch grid

patch_H = H // self.patch_size

patch_W = W // self.patch_size

# --- 1. Get Encoder Features ---

# features is a list of 4 tensors, as specified by out_indices=[2, 5, 8, 11]

# Each tensor has shape [B, N, C], where N = patch_H * patch_W and C = embed_dim

# Example: [B, 3136, 768] for an 896x896 input

features: List[torch.Tensor] = self.encoder(x)

# --- 2. Reshape and Concatenate ---

# We need to reshape the patch tokens back into a 2D spatial grid

# From [B, N, C] -> [B, C, H_patch, W_patch]

reshaped_features = []

for f in features:

# f.permute(0, 2, 1) -> [B, C, N]

# .reshape(...) -> [B, C, H_patch, W_patch]

f_reshaped = f.permute(0, 2, 1).reshape(B, self.embed_dim, patch_H, patch_W)

reshaped_features.append(f_reshaped)

# Concatenate along the channel dimension

# 4 * [B, 768, 56, 56] -> [B, 768*4, 56, 56]

x_cat = torch.cat(reshaped_features, dim=1)

# --- 3. Decode Features ---

# The decoder upsamples from [B, 768*4, 56, 56] to [B, num_classes, 896, 896]

segmentation_map = self.decoder(x_cat)

# The decoder output might not be *exactly* the input size due to

# transpose conv padding. We use interpolation to resize it cleanly.

segmentation_map = F.interpolate(

segmentation_map,

size=(H, W),

mode='bilinear',

align_corners=False

)

return segmentation_map

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Test the model with a dummy input

# The paper trains at 896x896 resolution

# AMOS22 dataset has 15 organs

num_classes = 15

model = MedDINOv3_Segmentor(num_classes=num_classes)

# Create a random input tensor

# Batch size = 2, Channels = 3 (RGB), Height = 896, Width = 896

dummy_input = torch.randn(2, 3, 896, 896)

print(f"Input shape: {dummy_input.shape}")

# Pass input through the model

with torch.no_grad():

output = model(dummy_input)

print(f"Output shape: {output.shape}")

# Check if output shape is correct

assert output.shape == (2, num_classes, 896, 896)

print("\nModel instantiated and test pass successful!")

print(f" Encoder: {model.encoder.model_name}")

print(f" Encoder Embed Dim: {model.embed_dim}")

print(f" Decoder Input Channels: {model.embed_dim * 4}")

print(f" Output Classes: {model.num_classes}")Related posts, You May like to read

- 7 Shocking Truths About Knowledge Distillation: The Good, The Bad, and The Breakthrough (SAKD)

- 7 Revolutionary Breakthroughs in Medical Image Translation (And 1 Fatal Flaw That Could Derail Your AI Model)

- TimeDistill: Revolutionizing Time Series Forecasting with Cross-Architecture Knowledge Distillation

- HiPerformer: A New Benchmark in Medical Image Segmentation with Modular Hierarchical Fusion

- GeoSAM2 3D Part Segmentation — Prompt-Controllable, Geometry-Aware Masks for Precision 3D Editing

- Probabilistic Smooth Attention for Deep Multiple Instance Learning in Medical Imaging

- A Knowledge Distillation-Based Approach to Enhance Transparency of Classifier Models

- Towards Trustworthy Breast Tumor Segmentation in Ultrasound Using AI Uncertainty

- Discrete Migratory Bird Optimizer with Deep Transfer Learning for Multi-Retinal Disease Detection

Pingback: SegTrans: The Breakthrough Framework That Makes AI Segmentation Models Vulnerable to Transfer Attacks - aitrendblend.com

Pingback: Revolutionizing Medical Imaging: How a Compact, Programmable Ultrasound Array Unlocks High-Contrast Elastography for Bones and Tumors - aitrendblend.com