In an era where privacy concerns and environmental limitations increasingly challenge traditional video-based biometric systems, a sophisticated new approach to human identification is emerging from the intersection of radar technology and deep learning. Video-based gait recognition, while successful in many applications, suffers from significant limitations including potential privacy issues and performance degradation due to dim environments, partial occlusions, or camera view changes.

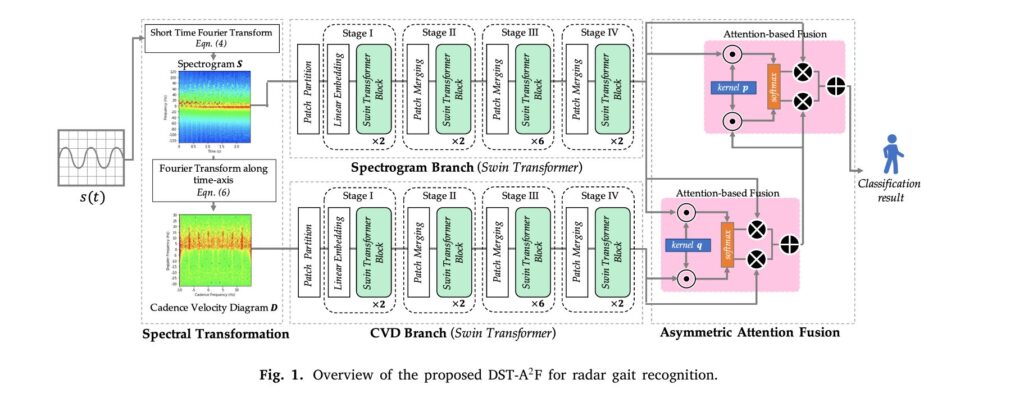

The solution lies in an unexpected direction: using radar signals to create biometric signatures based on human walking patterns. Researchers have developed a groundbreaking method called the Dual-branch Swin Transformer with Asymmetric Attention Fusion (DST-A²F), which represents a fundamental shift in how machines can identify individuals without ever recording their image. This article explores the technical innovation, practical implications, and future applications of this transformative technology.

Understanding Radar-Based Gait Recognition: The Fundamentals

Why Radar Over Video Cameras?

The advantages of radar-based gait recognition extend far beyond privacy protection. Radar has recently become increasingly popular and overcome various challenges presented by vision sensors, offering multiple compelling benefits that traditional approaches simply cannot match:

- Privacy preservation: No facial features, clothing details, or identifying visual information is recorded

- Environmental robustness: Radars work well in dim light or extreme weather conditions while video cameras cannot

- Frontal-view capability: Unlike cameras, radar effectively captures gait patterns when individuals move directly toward or away from the sensor

- Clothing invariance: Walking patterns detected through radar are unaffected by what a person is wearing

- Rapid feature extraction: Instantaneous human gait features can be extracted from radar signals, while GEIs are extracted from video sequences

Micro-Doppler Signatures: The Gait Fingerprint

At the heart of radar-based identification lies the concept of micro-Doppler signatures. When a person walks toward or away from a radar antenna, different body parts (arms, legs, torso) move at varying velocities. Each micro-motion produces distinct frequency shifts in the reflected radar signal—a phenomenon called the micro-Doppler effect. Radar micro-Doppler signature (mDS) has been widely utilized for automatic target recognition, e.g., UAV detection, pose estimation, activity recognition, and gait recognition.

Signal Processing Pipeline: From Raw Data to Spectral Representations

The transformation from raw radar signals to interpretable representations involves a sophisticated mathematical pipeline. The radar signal s(t)s(t) s(t) captured from a walking person undergoes segmentation into MM M non-overlapping segments:

where each segment xi = {xi [n],n=0,1,…,N−1} is a vector of length N. These segments form a synthetic image of size M×N. The Fourier transform is computed for each segment:

\[ f_{i,k} = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} x_i[n] \exp\left\{-j2\pi\frac{kn}{N}\right\} \]where F{⋅} denotes the Fourier transform. The magnitude spectrum forms the spectrogram:

\[ \mathbf{S} = \{|f_{i,k}|^2, \quad i = 0, 1, \ldots, M-1, \quad k = 0, 1, \ldots, N-1\} \]For the dataset described in the paper, N=128 with a Hamming window applied. Notably, no zero-padding or window overlapping is applied to preserve temporal resolution.

The Cadence Velocity Diagram (CVD) is generated by applying a Fourier transform along the time axis of the spectrogram:

\[ \mathbf{D} = \mathcal{F}_t\{\mathbf{S}\} \]where Ft{⋅} denotes the Fourier transform along the time axis. In implementation, M=115 with a rectangle window size of 128 and zero-padding applied. The CVD describes the periodic patterns of micro-Doppler components.

Table 1: Signal Processing Parameters and Specifications

\[ \begin{array}{|l|c|c|l|} \hline \textbf{Parameter} & \textbf{Spectrogram} & \textbf{CVD} & \textbf{Physical Interpretation} \\ \hline \text{Time axis segments (M)} & 115 & 115 & \text{Number of time windows during capture} \\ \hline \text{Frequency bins (N)} & 128 & 128 & \text{Doppler frequency resolution} \\ \hline \text{Window function} & \text{Hamming} & \text{Rectangle} & \text{Spectral leakage suppression} \\ \hline \text{Sampling rate (original)} & 125\,\text{kHz} & 125\,\text{kHz} & \text{Raw signal sampling frequency} \\ \hline \text{Sampling rate (decimated)} & 1.95\,\text{kHz} & 1.95\,\text{kHz} & \text{After decimation factor of 64} \\ \hline \text{Input image size} & 115\times115 & 115\times115 & \text{Processed representation dimensions} \\ \hline \text{Resized to} & 224\times224 & 224\times224 & \text{Network input requirement} \\ \hline \text{Zero-padding} & \text{No} & \text{Yes} & \text{Temporal/frequency padding} \\ \hline \text{Window overlap} & \text{No} & \text{Yes} & \text{Spectral analysis property} \\ \hline \end{array} \]The Dual-Branch Architecture: Extracting Complementary Features

Spectrogram and Cadence Velocity Diagram Representations

The DST-A²F system processes radar data into two complementary visual representations, each capturing different aspects of gait characteristics:

Spectrograms represent the time-varying frequency content of the radar signal, showing how micro-Doppler signatures evolve throughout a complete walking cycle. They reveal fine-grained details about micro-motion patterns—the subtle velocity changes of individual body segments as a person walks.

Cadence Velocity Diagrams (CVDs), conversely, emphasize the periodic and repetitive nature of human gait. Generated by applying a Fourier transform along the time axis of the spectrogram, the CVD describes the periodic patterns of micro-Doppler components and measures how frequently different Doppler frequencies appear in the spectrogram over the observation window.

The paper illustrates this complementarity through compelling visual examples. Two individuals with superficially similar spectrograms—indicating comparable micro-motion patterns—may display distinctly different cadence patterns in their CVDs. Conversely, two people with similar cadence frequencies may reveal their differences through spectrogram details. This synergy motivated the dual-branch design.

Why Swin Transformers Excel for Radar Data

Traditional convolutional neural networks treat spectrograms as natural images, applying operations designed for photographs. However, radar representations fundamentally differ from natural images. In a photograph, objects can be translated, rotated, or scaled, but in a spectrogram, the spatial coordinates carry precise physical meaning: one axis represents Doppler frequency (velocity), and the other represents time. Feature pooling operations in DCNNs may lose this critical global positional information.

The Swin Transformer addresses this architectural mismatch through its hierarchical design and local attention mechanisms:

- Patch-based processing: The spectrogram or CVD is divided into patches, each representing a specific frequency band during a specific time interval—preserving physical meaning

- Multi-scale feature extraction: Through hierarchical stages, the network learns features at different temporal and frequency resolutions

- Shifted window attention: Instead of full self-attention across the entire image, the Swin Transformer computes attention within local windows and shifts these windows cyclically, enabling cross-window interactions while maintaining computational efficiency

- Receptive field hierarchy: Swin-T can better model local and global time–frequency features through its hierarchical design that splits and merges patches at multiple scales to extract features from multiple receptive fields

Swin Transformer Architecture Specifications

Table 2: Swin Transformer Architecture Configuration

\[ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Stage} & \textbf{Input Resolution} & \textbf{Window Size} & \textbf{Swin Block Layers} & \textbf{Heads} & \textbf{Embed Dim / Output Channels} \\ \hline 1 & 56 \times 56 & 7 \times 7 & 2 & 3 & 96 \\ \hline 2 & 28 \times 28 & 7 \times 7 & 2 & 6 & 192 \\ \hline 3 & 14 \times 14 & 7 \times 7 & 6 & 12 & 384 \\ \hline 4 & 7 \times 7 & 7 \times 7 & 2 & 24 & 768 \\ \hline \end{array} \]The patch partition mechanism divides the input spectrogram/CVD of size 224×224224 \times 224 224×224 into non-overlapping patches of size 4×44 \times 4 4×4, resulting in 56×5656 \times 56 56×56 patches. The linear embedding layer projects each patch to the embedding dimension.

Window-Based Multi-Head Self-Attention

The Swin Transformer computes attention within local windows rather than globally across the entire feature map. The attention mechanism operates as:

\[ text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} + B\right)\mathbf{V} \]where Q, K, V are the query, key, and value projections, dk is the embedding dimension, and B is the relative position bias specific to each window. This local attention reduces computational complexity from O(N2) to O(NM2), where N is the number of patches and M is the window size.

Shifted window partitioning enables cross-window connections by alternating between regular and shifted window arrangements across consecutive blocks:

\[ \text{Attention}_{\text{shifted}} = \text{Attention}(\text{Shifted-Patches}) \]This mechanism allows patches to attend to neighbors in adjacent windows while maintaining the computational efficiency of local attention.

Table 3: Computational Complexity Comparison

\[ \begin{array}{|l|c|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Operation} & \textbf{Standard ViT} & \textbf{Swin Transformer} & \textbf{Reduction Factor} \\ \hline \text{Attention complexity} & O(4N^{2}) & O(4NM^{2}) & M^{2} / N \\ \hline \text{FLOPs (224 x 224 input)} & \sim 16.5\,G & \sim 5.95\,G & 2.77\times \\ \hline \text{Inference time (s)} & 109.545 & 52.16 & 2.10\times \\ \hline \text{Training time (s/epoch)} & 292.33 & 140.80 & 2.07\times \\ \hline \end{array} \]The Asymmetric Attention Fusion Mechanism

Beyond Equal-Weight Feature Combination

A critical innovation in DST-A²F lies in how it combines features from the spectrogram and CVD branches. Traditional fusion approaches treat both feature sources equally, learning to weight them based solely on input data. However, this data-driven approach overlooks valuable prior knowledge about feature importance.

Empirical studies show that the spectrogram outperforms the CVD for radar target recognition, and hence larger weights should be assigned to the spectrogram features for a better performance. Rather than forcing the network to re-discover this relationship during training, the DST-A²F architecture explicitly incorporates this knowledge.

Mathematical Framework of Asymmetric Attention Fusion

The fusion mechanism builds upon Element-wise Attention Fusion (EAF), which uses Hadamard products rather than matrix multiplication. For traditional attention-based fusion, learnable weights are derived as:

\[ w_i = \sigma(\mathbf{q}^T\mathbf{a}_i) = \frac{\exp(\mathbf{q}^T\mathbf{a}_i)}{\sum_{j}\exp(\mathbf{q}^T\mathbf{a}_j)} \]where σ(⋅) is the softmax function and q is a learnable kernel. The fusion output is derived as:

\[ \mathbf{a}_{AF} = \sum_{i=1}^{B} w_i\mathbf{a}_i \]where aAF contains partial attentive information from all B sets of features, and the optimal weights are automatically determined by the input features.

Element-wise Attention Fusion (EAF)

The EAF mechanism improves upon this by replacing matrix multiplication with Hadamard product:

\[ \mathbf{w}_i = \tilde{\sigma}(\mathbf{q} \odot \mathbf{a}_i) = \frac{\exp (\mathbf{q} \odot \mathbf{a}_i)}{\sum_{j} \exp(\mathbf{q} \odot \mathbf{a}_j)} \]where ⊙ denotes element-wise (Hadamard) production and ⊘ denotes element-wise division. The softmax function σ~ is also conducted element-wise. The fused feature is derived as:

\[ \mathbf{a}_{EAF} = \sum_{i=1}^{B} \mathbf{w}_i \odot \mathbf{a}_i \]where B=2 in the dual-branch task.

Asymmetric Attention Fusion (A²F)

The balanced fusion mechanism is well-suited when features carry equal or similar importance. However, in many tasks, prior knowledge about feature importance exists. Let EAF (fS, fD) denote the Element-wise Attention Fusion for spectrogram features fS and CVD features fD. The features fa after the proposed A²F are derived as:

\[ \mathbf{f}_a = \text{EAF}(\mathbf{f}_S, \text{EAF}(\mathbf{f}_S, \mathbf{f}_D)) \]This iterative application applies EAF with the prior knowledge that spectrogram features are more important. Since spectrogram features are weighted twice in the proposed A²F, they are assigned a higher importance than CVD features, which appear once.

Table 4: Fusion Mechanism Comparison

\[ \small \begin{array}{|l|c|c|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Fusion Method} & \textbf{Formula} & \textbf{Params} & \textbf{Weighting} & \textbf{Prior} \\ \hline \text{Concatenation} & [\mathbf{a}_1,\mathbf{a}_2] & \text{None} & \text{Equal} & \text{None} \\ \hline \text{Averaging} & \frac{1}{2}(\mathbf{a}_1+\mathbf{a}_2) & \text{None} & \text{Equal} & \text{None} \\ \hline \text{Max Pooling} & \max(\mathbf{a}_1,\mathbf{a}_2) & \text{None} & \text{Data-dep.} & \text{None} \\ \hline \text{Attention Fusion} & \sum_i w_i\mathbf{a}_i & 1 \text{ vector} & \text{Per-sample} & \text{None} \\ \hline \text{EAF} & \sum_i\mathbf{w}_i\odot\mathbf{a}_i & D & \text{Per-dim} & \text{None} \\ \hline \text{A}^{2}\text{F (Proposed)} & \text{EAF}(\mathbf{f}_S,\text{EAF}(\mathbf{f}_S,\mathbf{f}_D)) & D & \text{Per-dim} & \text{Spec.\ dom.} \\ \hline \end{array} \]The key advantage of A²F is the explicit incorporation of domain knowledge through iterative fusion, which empirical studies confirm produces superior results compared to balanced fusion approaches.

The NTU-RGR Dataset: A Large-Scale Benchmark

Dataset Construction and Protocol Design

A large-scale NTU-RGR dataset is constructed, containing 45,768 radar frames of 98 subjects. This represents a substantial resource for radar gait recognition research, collected under carefully controlled experimental conditions.

The data collection employed a 24.125 GHz K-MC1 FMCW radar transceiver in a 40-meter corridor. Each participant walked away from the radar from a starting point 0.5 meters away until reaching 25 meters distance, then returned, completing one full recording. Each recording lasted approximately 30 seconds, during which individuals were encouraged to walk naturally.

The dataset uniquely features two recording sessions separated by 7 to 62 days, deliberately introducing intra-class variations from changes in clothing, physical condition, and environmental factors—simulating real-world deployment scenarios.

Table 5: NTU-RGR Dataset Specifications

\[ \begin{array}{|l|c|l|} \hline \textbf{Property} & \textbf{Value} & \textbf{Description} \\ \hline \text{Total subjects} & 98 & \text{Diverse population (age 19–56, avg. 24)} \\ \hline \text{Recording sessions} & 2 & \text{Session 1: 98 subjects; Session 2: 69 subjects} \\ \hline \text{Total recordings} & 1,670 & \text{Complete walking sequences} \\ \hline \text{Total frames} & 45,768 & \text{After extraction with stride 10} \\ \hline \text{Frame dimensions} & 115\times115 & \text{After spectral processing} \\ \hline \text{Radar frequency} & 24.125\ \text{GHz} & \text{K-MC1 FMCW transceiver} \\ \hline \text{Radar sampling rate} & 125\ \text{kHz} & \text{Original sampling frequency} \\ \hline \text{Decimation factor} & 64 & \text{Reduces effective SR to 1.95 kHz} \\ \hline \text{Recording duration} & \sim30\ \text{s} & \text{Per complete walk cycle} \\ \hline \text{Walking distance} & 0.5{-}25\ \text{m} & \text{Away and back toward radar} \\ \hline \text{Corridor length} & 40\ \text{m} & \text{Controlled indoor environment} \\ \hline \text{Frame stride} & 10 & \text{Controls temporal overlap} \\ \hline \text{Inter-session interval} & 7{-}62\ \text{days} & \text{Clothing / condition variation} \\ \hline \end{array} \]Evaluation Protocols: Closed-Set and Open-Set Recognition

Two distinct evaluation protocols address different security scenarios:

Table 6: Evaluation Protocols and Metrics

\[ \begin{array}{|l|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Aspect} & \textbf{Closed-Set Recognition} & \textbf{Open-Set Recognition} \\ \hline \text{Description} & \text{All test subjects appear in training data} & \text{Test includes unknown imposters} \\ \hline \text{Real-world application} & \text{Authorized personnel identification} & \text{Border security, threat detection} \\ \hline \text{Training set} & \text{50\% of recordings per person (random)} & \text{Remaining recordings from Session 1} \\ \hline \text{Test set (genuine)} & \text{50\% of recordings per person} & \text{All recordings from Session 2} \\ \hline \text{Imposter set} & \text{None} & \text{Session 1 recordings not in training} \\ \hline \text{Training frames} & 18,950 & 18,950 \\ \hline \text{Test frames (genuine)} & \text{Variable} & \text{Variable} \\ \hline \text{Test frames (imposter)} & \text{N/A} & 7,868 \\ \hline \text{Evaluation metric} & \text{Rank-1 accuracy} & \text{\% genuine accepted + imposters rejected} \\ \hline \text{Difficulty level} & \text{Moderate} & \text{High (confidence-based rejection)} \\ \hline \text{Practical challenge} & \text{Recognizing known individuals} & \text{Distinguishing known vs unknown} \\ \hline \text{Number of trials} & 5\ (\text{avg.}) & 2\ (\text{protocol-specific}) \\ \hline \end{array} \]Closed-set recognition is simpler—the network only needs to correctly classify among known subjects. Open-set recognition is significantly more challenging, as it requires the model to not only recognize genuine subjects but also reject unknown imposters based on relatively low confidence scores.

Experimental Results: Achieving State-of-the-Art Performance

Comprehensive Benchmark Comparisons

The DST-A²F architecture substantially outperformed established baselines and recent methods. The proposed DST-A²F achieved 95.96% accuracy on Protocol I (closed-set) and 54.46% on Protocol II (open-set). The 7.53% improvement over ADS-ViT on Protocol I and 6.89% on Protocol II demonstrates the effectiveness of combining Swin Transformer architecture with asymmetric attention fusion.

Performance Analysis by Architecture Component

Table 8: Ablation Study Results – Component Contribution Analysis

\[ \small \begin{array}{|l|c|c|c|c|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Model Config.} & \textbf{Backbone} & \textbf{Spec} & \textbf{CVD} & \textbf{Fusion} & \textbf{Protocol I (\%)} & \textbf{Protocol II (\%)} \\ \hline \text{Baseline: Spec+ViT} & \text{ViT} & \checkmark & \times & \text{N/A} & 84.64 \pm 1.66 & 46.06 \pm 2.49 \\ \hline \text{CVD+ViT} & \text{ViT} & \times & \checkmark & \text{N/A} & 80.27 \pm 2.47 & 41.31 \pm 1.06 \\ \hline \text{Spec+Swin-T} & \text{Swin-T} & \checkmark & \times & \text{N/A} & 94.25 \pm 0.62 & 49.38 \pm 0.48 \\ \hline \text{CVD+Swin-T} & \text{Swin-T} & \times & \checkmark & \text{N/A} & 87.12 \pm 0.75 & 43.42 \pm 0.18 \\ \hline \text{ADS-ViT} & \text{ViT} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \text{EAF} & 88.43 \pm 1.03 & 47.57 \pm 0.50 \\ \hline \text{Dual-branch ViT + A^{2}F} & \text{ViT} & \checkmark & \checkmark & A^{2}F & 89.26 \pm 0.89 & 48.31 \pm 0.75 \\ \hline \text{Dual-branch Swin-T + EAF} & \text{Swin-T} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \text{EAF} & 95.01 \pm 0.45 & 52.41 \pm 0.53 \\ \hline \text{Full DST-A^{2}F} & \text{Swin-T} & \checkmark & \checkmark & A^{2}F & 95.96 \pm 0.42 & 54.46 \pm 0.67 \\ \hline \end{array} \]Key observations from the ablation study:

- Swin-T superiority: Upgrading from ViT to Swin-T improves accuracy by 9.61% on spectrograms alone and 6.85% on CVDs alone

- Fusion complementarity: Combining spectrogram and CVD branches provides 4.62% improvement over spectrogram-only with ViT and 1.71% with Swin-T

- Asymmetric advantage: A²F adds 0.95% improvement over balanced EAF on Swin-T, validating the value of incorporating prior knowledge

Backbone Architecture Comparative Analysis

Table 9: Backbone Architecture Performance Comparison

\[ \begin{array}{|l|l|c|c|c|c|} \hline \text{Backbone} & \text{Input Type} & \text{Protocol I (\%)} & \text{Protocol II (\%)} & \text{Spec vs. CVD Gap} & \text{Dual-branch Gain} \\ \hline \text{AlexNet} & \text{Spec} & 72.49 \pm 1.54 & 32.55 \pm 1.15 & -10.00 & +13.24 \\ & \text{CVD} & 82.49 \pm 1.49 & 34.29 \pm 2.93 & – & – \\ & \text{Dual} & 85.73 \pm 1.16 & 37.05 \pm 2.55 & – & – \\ \hline \text{VGG} & \text{Spec} & 78.90 \pm 1.96 & 46.38 \pm 2.09 & +6.01 & +5.19 \\ & \text{CVD} & 72.89 \pm 1.40 & 36.14 \pm 0.86 & – & – \\ & \text{Dual} & 84.09 \pm 1.07 & 46.73 \pm 1.49 & – & – \\ \hline \text{ResNet} & \text{Spec} & 86.05 \pm 1.27 & 46.48 \pm 1.69 & +5.38 & +4.63 \\ & \text{CVD} & 80.67 \pm 1.11 & 39.28 \pm 0.45 & – & – \\ & \text{Dual} & 90.68 \pm 0.91 & 47.53 \pm 1.93 & – & – \\ \hline \text{EfficientNet} & \text{Spec} & 90.92 \pm 1.07 & 47.91 \pm 1.12 & +4.81 & +2.88 \\ & \text{CVD} & 86.11 \pm 0.53 & 41.24 \pm 1.63 & – & – \\ & \text{Dual} & 93.80 \pm 0.68 & 50.01 \pm 0.45 & – & – \\ \hline \text{ViT} & \text{Spec} & 84.64 \pm 1.66 & 46.06 \pm 2.49 & +4.37 & +4.62 \\ & \text{CVD} & 80.27 \pm 2.47 & 41.31 \pm 1.06 & – & – \\ & \text{Dual} & 89.26 \pm 0.89 & 48.31 \pm 0.75 & – & – \\ \hline \text{Swin-T} & \text{Spec} & 94.25 \pm 0.62 & 49.38 \pm 0.48 & +7.13 & +1.71 \\ & \text{CVD} & 87.12 \pm 0.75 & 43.42 \pm 0.18 & – & – \\ & \text{Dual} & 95.96 \pm 0.42 & 54.46 \pm 0.67 & – & – \\ \hline \end{array} \]The analysis reveals that Swin-T achieves the best balance of accuracy and computational efficiency, with the largest spectrogram-to-CVD performance gap suggesting that the hierarchical architecture particularly benefits spectrogram feature extraction.

Fusion Mechanism Detailed Comparison

Table 10: Fusion Mechanism Performance on Dual-branch Swin-T

\[ \small \begin{array}{|l|c|c|c|c|} \hline \text{Fusion Mechanism} & \text{Protocol I Accuracy } & \text{Protocol II Accuracy } & \text{Accuracy Improvement (P1)} & \text{Accuracy Improvement (P2)} \\ \hline \text{Feature max pooling} & 94.44 \pm 0.56 & 48.85 \pm 3.88 & -1.52 & -5.61 \\ \text{Feature min pooling} & 94.42 \pm 0.63 & 49.16 \pm 2.05 & -1.54 & -5.30 \\ \text{Feature concatenation} & 94.99 \pm 0.73 & 51.87 \pm 1.63 & -0.97 & -2.59 \\ \text{Feature averaging} & 94.19 \pm 0.44 & 49.67 \pm 0.83 & -1.77 & -4.79 \\ \text{Attention-based fusion} & 93.49 \pm 2.72 & 46.89 \pm 2.19 & -2.47 & -7.57 \\ \text{EAF (Element-wise Attention)} & 95.01 \pm 0.45 & 52.41 \pm 0.53 & -0.95 & -2.05 \\ \text{A²F (Asymmetric Attention)} & 95.96 \pm 0.42 & 54.46 \pm 0.67 & \text{Baseline} & \text{Baseline} \\ \hline \end{array} \]The A²F mechanism significantly outperforms all alternatives, with the largest margins over simple fusion strategies (concatenation, averaging) and meaningful improvements over the previously best method (EAF). This validates the theoretical expectation that incorporating prior knowledge about feature importance enhances fusion effectiveness.

Cross-Dataset Validation: MMRGait-1.0 Performance

To validate generalization beyond the NTU-RGR dataset, researchers evaluated DST-A²F on the public MMRGait-1.0 benchmark.

Table 11: Multi-View Recognition Performance on MMRGait-1.0 Dataset

\[ \small \begin{array}{|l|c|c|c|c|c|} \hline \text{Wearing Condition} & \text{View Angles} & \text{ResNet50 (%)} & \text{EfficientNet (%)} & \text{ADS-ViT (%)} & \text{MS-R18-LST-SA (%)} & \text{DST-A²F (%)} \\ \hline \text{NM (Normal Wearing)} & 0^\circ & 95.74 & 93.62 & 95.74 & 91.86 & 97.87 \\ & 30^\circ & 93.62 & 89.36 & 94.68 & 94.19 & 96.80 \\ & 45^\circ & 91.49 & 96.80 & 94.68 & 96.51 & 97.87 \\ & 60^\circ & 93.62 & 92.55 & 93.62 & 94.19 & 96.80 \\ & 90^\circ & 84.04 & 82.98 & 86.17 & 91.86 & 86.17 \\ & 300^\circ & 89.36 & 90.43 & 93.62 & 98.84 & 96.80 \\ & 315^\circ & 93.62 & 91.49 & 93.62 & 91.86 & 98.94 \\ & 330^\circ & 92.55 & 90.43 & 94.68 & 96.51 & 95.74 \\ \hline \text{NM Average} & – & 91.76 & 90.96 & 93.35 & 94.48 & 95.88 \\ \hline \text{BG (Carrying Bags) Average} & – & 77.53 & 81.38 & 76.33 & 81.25 & 88.03 \\ \hline \text{CT (Wearing Coats) Average} & – & 75.80 & 76.86 & 77.93 & 79.21 & 82.98 \\ \hline \end{array} \]The proposed DST-A²F significantly outperforms others, achieving an average performance gain of 1.4% on normal wearing (NM), 6.78% on carrying bags (BG), and 3.77% on wearing coats (CT) compared to the previous best method MS-R18-LST-SA. Notably, the method struggles at 90° viewing angle where side-view gait contains fewer discriminative features, suggesting a direction for future improvement through multi-modal fusion.

Key Takeaways: Why This Matters

🎯 Privacy-First Biometrics: Unlike facial recognition or gait videos, radar-based identification requires no visual data storage, addressing the privacy concerns that plague modern surveillance systems.

🎯 All-Weather Reliability: The robustness to lighting conditions, fog, rain, and other environmental factors makes radar gait recognition viable for outdoor security applications where video fails.

🎯 Technical Innovation: The combination of Swin Transformers with asymmetric attention fusion demonstrates how architectural design can encode domain knowledge and improve performance meaningfully.

🎯 Practical Validation: Achievement of 95%+ accuracy on closed-set recognition suggests deployment readiness for authorized personnel identification in controlled environments.

Conclusion: The Future of Biometric Security

The DST-A²F architecture represents a paradigm shift in biometric authentication, prioritizing privacy, robustness, and technical sophistication over traditional video-centric approaches. By leveraging radar micro-Doppler signatures through advanced deep learning architectures, researchers have demonstrated that human identification can occur without any visual data—addressing fundamental privacy concerns while maintaining competitive accuracy.

As security systems increasingly grapple with balancing identification capability against privacy rights, radar-based gait recognition offers a compelling alternative worthy of serious consideration for access control, border security, and personnel identification applications.

What aspects of radar-based security interest you most? Are you concerned about privacy implications of traditional surveillance systems? Share your thoughts in the comments below—let’s discuss how emerging technologies can reshape security for a more privacy-respecting future.

Download the full paper and read it to click this link.

Below is the comprehensive implementation of the Dual-branch Swin Transformer with Asymmetric Attention Fusion (DST-A²F) model for radar gait recognition.

# config.py

"""

Configuration management for DST-A2F model

"""

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Tuple, Optional

import yaml

import os

@dataclass

class RadarSignalConfig:

"""Radar signal processing configuration"""

sampling_rate: int = 125000 # Original sampling rate in Hz

decimation_factor: int = 64 # Decimation for computational efficiency

fft_size: int = 128 # FFT window size for spectrogram

n_segments: int = 115 # Number of time segments

window_function: str = "hamming" # Window type for FFT

@property

def effective_sampling_rate(self) -> int:

return self.sampling_rate // self.decimation_factor

@dataclass

class DataProcessingConfig:

"""Data processing configuration"""

spectrogram_size: Tuple[int, int] = (115, 115)

cvd_size: Tuple[int, int] = (115, 115)

input_size: Tuple[int, int] = (224, 224) # Resized input for network

num_classes: int = 98 # NTU-RGR dataset

train_split: float = 0.5

frame_stride: int = 10 # Stride for frame extraction

@dataclass

class ModelConfig:

"""Model architecture configuration"""

# Swin Transformer parameters

patch_size: int = 4

window_size: int = 7

embed_dim: int = 96

depths: Tuple[int, ...] = (2, 2, 6, 2) # Layers per stage

num_heads: Tuple[int, ...] = (3, 6, 12, 24) # Attention heads per stage

mlp_ratio: float = 4.0

dropout: float = 0.1

attention_dropout: float = 0.0

drop_path_rate: float = 0.2

# Fusion parameters

fusion_type: str = "asymmetric_attention" # "concatenation", "attention", "asymmetric_attention"

num_branches: int = 2

@dataclass

class TrainingConfig:

"""Training configuration"""

batch_size: int = 32

num_epochs: int = 150

initial_lr: float = 1e-4

weight_decay: float = 5e-2

optimizer: str = "sgd"

warmup_epochs: int = 10

device: str = "cuda"

num_workers: int = 4

seed: int = 42

# Learning rate scheduler

scheduler: str = "cosine" # "cosine", "step", "exponential"

# Checkpointing

checkpoint_dir: str = "./checkpoints"

log_dir: str = "./logs"

save_interval: int = 10

@dataclass

class DST_A2FConfig:

"""Complete configuration for DST-A²F model"""

radar_signal: RadarSignalConfig = None

data_processing: DataProcessingConfig = None

model: ModelConfig = None

training: TrainingConfig = None

def __post_init__(self):

if self.radar_signal is None:

self.radar_signal = RadarSignalConfig()

if self.data_processing is None:

self.data_processing = DataProcessingConfig()

if self.model is None:

self.model = ModelConfig()

if self.training is None:

self.training = TrainingConfig()

@classmethod

def from_yaml(cls, yaml_path: str) -> 'DST_A2FConfig':

"""Load configuration from YAML file"""

with open(yaml_path, 'r') as f:

config_dict = yaml.safe_load(f)

return cls(

radar_signal=RadarSignalConfig(**config_dict.get('radar_signal', {})),

data_processing=DataProcessingConfig(**config_dict.get('data_processing', {})),

model=ModelConfig(**config_dict.get('model', {})),

training=TrainingConfig(**config_dict.get('training', {}))

)

def to_yaml(self, yaml_path: str) -> None:

"""Save configuration to YAML file"""

config_dict = {

'radar_signal': self.radar_signal.__dict__,

'data_processing': self.data_processing.__dict__,

'model': self.model.__dict__,

'training': self.training.__dict__,

}

os.makedirs(os.path.dirname(yaml_path), exist_ok=True)

with open(yaml_path, 'w') as f:

yaml.dump(config_dict, f, default_flow_style=False)

# config.yaml

radar_signal:

sampling_rate: 125000

decimation_factor: 64

fft_size: 128

n_segments: 115

window_function: "hamming"

data_processing:

spectrogram_size: [115, 115]

cvd_size: [115, 115]

input_size: [224, 224]

num_classes: 98

train_split: 0.5

frame_stride: 10

model:

patch_size: 4

window_size: 7

embed_dim: 96

depths: [2, 2, 6, 2]

num_heads: [3, 6, 12, 24]

mlp_ratio: 4.0

dropout: 0.1

attention_dropout: 0.0

drop_path_rate: 0.2

fusion_type: "asymmetric_attention"

num_branches: 2

training:

batch_size: 32

num_epochs: 150

initial_lr: 0.0001

weight_decay: 0.05

optimizer: "sgd"

warmup_epochs: 10

device: "cuda"

num_workers: 4

seed: 42

scheduler: "cosine"

checkpoint_dir: "./checkpoints"

log_dir: "./logs"

save_interval: 10# signal_processing.py

"""

Radar signal processing utilities for generating spectrograms and CVDs

"""

import numpy as np

from scipy import signal

from scipy.fft import fft, fftfreq

from typing import Tuple, Optional

import torch

class RadarSignalProcessor:

"""

Process raw radar signals into spectrograms and Cadence Velocity Diagrams

"""

def __init__(

self,

sampling_rate: int = 125000,

decimation_factor: int = 64,

fft_size: int = 128,

n_segments: int = 115,

window_type: str = "hamming"

):

"""

Initialize radar signal processor

Args:

sampling_rate: Original sampling rate in Hz

decimation_factor: Decimation factor

fft_size: FFT window size

n_segments: Number of time segments

window_type: Window function type

"""

self.sampling_rate = sampling_rate

self.decimation_factor = decimation_factor

self.effective_sr = sampling_rate // decimation_factor

self.fft_size = fft_size

self.n_segments = n_segments

self.window_type = window_type

# Create window function

self.window = signal.get_window(window_type, fft_size)

def generate_spectrogram(

self,

raw_signal: np.ndarray,

overlap: bool = False

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Generate spectrogram from raw radar signal

Mathematical formulation:

S = {|F{x_i}|^2, i = 0, 1, ..., M-1}

where F{·} denotes Fourier transform and M is number of segments

Args:

raw_signal: Raw radar signal (1D array)

overlap: Whether to use overlapping windows

Returns:

Spectrogram of shape (n_segments, fft_size)

"""

# Decimate signal

decimated_signal = raw_signal[::self.decimation_factor]

# Segment signal

segment_length = self.fft_size

segments = []

for i in range(self.n_segments):

start_idx = i * segment_length

end_idx = start_idx + segment_length

if end_idx <= len(decimated_signal):

segment = decimated_signal[start_idx:end_idx]

segments.append(segment)

else:

# Pad with zeros if necessary

segment = np.zeros(segment_length)

valid_len = len(decimated_signal) - start_idx

if valid_len > 0:

segment[:valid_len] = decimated_signal[start_idx:]

segments.append(segment)

# Stack segments

signal_matrix = np.array(segments) # Shape: (n_segments, fft_size)

# Apply window function

windowed_signal = signal_matrix * self.window[np.newaxis, :]

# Compute FFT for each segment

fft_result = np.fft.fft(windowed_signal, axis=1)

# Compute magnitude squared

spectrogram = np.abs(fft_result) ** 2

return spectrogram.astype(np.float32)

def generate_cvd(

self,

spectrogram: np.ndarray,

zero_pad: bool = True

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Generate Cadence Velocity Diagram (CVD) from spectrogram

Mathematical formulation:

D = F_t{S}

where F_t{·} denotes Fourier transform along time axis

Args:

spectrogram: Input spectrogram

zero_pad: Whether to apply zero-padding

Returns:

CVD of shape (n_segments, fft_size)

"""

# Apply FFT along time axis (axis 0)

if zero_pad:

# Zero-pad for spectral analysis

padded_spec = np.pad(spectrogram, ((0, self.fft_size), (0, 0)), mode='constant')

cvd_result = np.fft.fft(padded_spec, axis=0)

else:

cvd_result = np.fft.fft(spectrogram, axis=0)

# Compute magnitude

cvd = np.abs(cvd_result) ** 2

# Truncate to match input dimensions

cvd = cvd[:spectrogram.shape[0], :spectrogram.shape[1]]

return cvd.astype(np.float32)

def process_radar_frame(

self,

raw_signal: np.ndarray

) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

"""

Process raw radar signal into spectrogram and CVD

Args:

raw_signal: Raw radar signal

Returns:

Tuple of (spectrogram, cvd)

"""

spectrogram = self.generate_spectrogram(raw_signal)

cvd = self.generate_cvd(spectrogram)

return spectrogram, cvd

def normalize_image(

self,

image: np.ndarray,

method: str = "minmax"

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Normalize image to [0, 1] range

Args:

image: Input image

method: Normalization method ("minmax" or "standardize")

Returns:

Normalized image

"""

if method == "minmax":

min_val = image.min()

max_val = image.max()

if max_val > min_val:

return (image - min_val) / (max_val - min_val)

else:

return image

elif method == "standardize":

return (image - image.mean()) / (image.std() + 1e-7)

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unknown normalization method: {method}")

def resize_image(

self,

image: np.ndarray,

target_size: Tuple[int, int],

method: str = "bilinear"

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Resize image to target size

Args:

image: Input image

target_size: Target size (height, width)

method: Interpolation method

Returns:

Resized image

"""

from scipy import ndimage

# Handle different interpolation methods

if method == "bilinear":

order = 1

elif method == "nearest":

order = 0

elif method == "bicubic":

order = 3

else:

order = 1

# Compute scaling factors

scale_h = target_size[0] / image.shape[0]

scale_w = target_size[1] / image.shape[1]

# Resize using scipy

resized = ndimage.zoom(image, (scale_h, scale_w), order=order)

return resized.astype(np.float32)

# Example usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Create processor

processor = RadarSignalProcessor(

sampling_rate=125000,

decimation_factor=64,

fft_size=128,

n_segments=115,

window_type="hamming"

)

# Generate synthetic radar signal for testing

duration = 30 # seconds

t = np.linspace(0, duration, int(125000 * duration))

# Simulate micro-Doppler signatures with multiple frequency components

raw_signal = (

np.sin(2 * np.pi * 10 * t) + # 10 Hz walking frequency

0.5 * np.sin(2 * np.pi * 20 * t) + # Arm swing

0.3 * np.sin(2 * np.pi * 30 * t) + # Torso motion

0.1 * np.random.randn(len(t)) # Noise

)

# Process signal

spectrogram, cvd = processor.process_radar_frame(raw_signal)

print(f"Spectrogram shape: {spectrogram.shape}")

print(f"CVD shape: {cvd.shape}")

# Normalize and resize

spec_norm = processor.normalize_image(spectrogram)

spec_resized = processor.resize_image(spec_norm, (224, 224))

print(f"Resized spectrogram shape: {spec_resized.shape}")# fusion.py

"""

Asymmetric Attention Fusion (A²F) mechanism

"""

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

from typing import Tuple

class ElementwiseAttentionFusion(nn.Module):

"""

Element-wise Attention Fusion (EAF)

Weights features element-wise rather than using scalar weights,

allowing different feature dimensions to have different importance.

Mathematical formulation:

w_i = σ̃(q ⊙ a_i) = exp(q ⊙ a_i) ⊘ Σ_j exp(q ⊙ a_j)

a_EAF = Σ_i w_i ⊙ a_i

where ⊙ is element-wise product, ⊘ is element-wise division,

and σ̃ is element-wise softmax

"""

def __init__(self, feature_dim: int):

"""

Initialize Element-wise Attention Fusion

Args:

feature_dim: Dimension of feature vectors

"""

super().__init__()

self.feature_dim = feature_dim

self.learnable_kernel = nn.Parameter(torch.ones(1, feature_dim))

def forward(self, features: Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

Fuse two sets of features using element-wise attention

Args:

features: Tuple of (feature1, feature2), each of shape (B, D)

where B is batch size and D is feature dimension

Returns:

Fused features of shape (B, D)

"""

f1, f2 = features

batch_size = f1.shape[0]

# Element-wise product with learnable kernel

# w_1 = σ̃(q ⊙ f1)

w1_logits = self.learnable_kernel * f1 # (B, D)

w2_logits = self.learnable_kernel * f2 # (B, D)

# Element-wise softmax normalization

all_logits = torch.stack([w1_logits, w2_logits], dim=2) # (B, D, 2)

weights = F.softmax(all_logits, dim=2) # (B, D, 2)

w1 = weights[:, :, 0] # (B, D)

w2 = weights[:, :, 1] # (B, D)

# Fuse using element-wise products

fused = w1 * f1 + w2 * f2

return fused

class AsymmetricAttentionFusion(nn.Module):

"""

Asymmetric Attention Fusion (A²F)

Iteratively applies EAF to assign higher importance to the first branch.

This incorporates prior knowledge that one feature source is more

discriminative than the other.

Mathematical formulation:

f_a = EAF(f_S, EAF(f_S, f_D))

By applying spectrogram features (f_S) twice and CVD features (f_D) once,

spectrogram features are assigned higher importance.

"""

def __init__(self, feature_dim: int):

"""

Initialize Asymmetric Attention Fusion

Args:

feature_dim: Dimension of feature vectors

"""

super().__init__()

self.eaf = ElementwiseAttentionFusion(feature_dim)

def forward(

self,

features_primary: torch.Tensor,

features_secondary: torch.Tensor

) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

Fuse features asymmetrically, emphasizing primary features

Args:

features_primary: Primary features (e.g., spectrogram), shape (B, D)

features_secondary: Secondary features (e.g., CVD), shape (B, D)

Returns:

Fused features with asymmetric emphasis, shape (B, D)

"""

# First fusion: fuse primary and secondary

fused_1 = self.eaf((features_primary, features_secondary))

# Second fusion: fuse primary with first result

# This effectively weights primary features twice

fused_2 = self.eaf((features_primary, fused_1))

return fused_2

class AdaptiveFusion(nn.Module):

"""

Adaptive fusion mechanism that learns optimal combination strategy

"""

def __init__(

self,

feature_dim: int,

fusion_type: str = "asymmetric_attention"

):

"""

Initialize adaptive fusion

Args:

feature_dim: Dimension of feature vectors

fusion_type: Type of fusion ("concatenation", "attention",

"asymmetric_attention", "weighted_sum")

"""

super().__init__()

self.feature_dim = feature_dim

self.fusion_type = fusion_type

if fusion_type == "asymmetric_attention":

self.fusion_module = AsymmetricAttentionFusion(feature_dim)

elif fusion_type == "attention":

self.fusion_module = ElementwiseAttentionFusion(feature_dim)

elif fusion_type == "weighted_sum":

self.weight1 = nn.Parameter(torch.tensor(0.5))

self.weight2 = nn.Parameter(torch.tensor(0.5))

elif fusion_type == "concatenation":

self.fusion_module = None

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unknown fusion type: {fusion_type}")

def forward(

self,

features_1: torch.Tensor,

features_2: torch.Tensor

) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

Fuse two feature sets

Args:

features_1: First set of features

features_2: Second set of features

Returns:

Fused features

"""

if self.fusion_type == "asymmetric_attention":

return self.fusion_module(features_1, features_2)

elif self.fusion_type == "attention":

return self.fusion_module((features_1, features_2))

elif self.fusion_type == "weighted_sum":

# Normalize weights

w1 = F.softmax(torch.stack([self.weight1, self.weight2]), dim=0)[0]

w2 = F.softmax(torch.stack([self.weight1, self.weight2]), dim=0)[1]

return w1 * features_1 + w2 * features_2

elif self.fusion_type == "concatenation":

return torch.cat([features_1, features_2], dim=1)

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unknown fusion type: {self.fusion_type}")

# Test fusion modules

if __name__ == "__main__":

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Create test tensors

batch_size = 8

feature_dim = 768

f1 = torch.randn(batch_size, feature_dim).to(device)

f2 = torch.randn(batch_size, feature_dim).to(device)

# Test EAF

eaf = ElementwiseAttentionFusion(feature_dim).to(device)

fused_eaf = eaf((f1, f2))

print(f"EAF output shape: {fused_eaf.shape}")

# Test A²F

a2f = AsymmetricAttentionFusion(feature_dim).to(device)

fused_a2f = a2f(f1, f2)

print(f"A²F output shape: {fused_a2f.shape}")

# Test Adaptive Fusion

adaptive = AdaptiveFusion(feature_dim, "asymmetric_attention").to(device)

fused_adaptive = adaptive(f1, f2)

print(f"Adaptive fusion output shape: {fused_adaptive.shape}")# swin_transformer.py

"""

Swin Transformer implementation for radar gait recognition

"""

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from timm.models.swin_transformer import SwinTransformer

from typing import Tuple, Optional

import torch.nn.functional as F

class SwinTransformerExtractor(nn.Module):

"""

Swin Transformer feature extractor

Extracts multi-scale features from spectrograms/CVDs using hierarchical

Swin Transformer architecture with shifted window attention.

"""

def __init__(

self,

image_size: int = 224,

patch_size: int = 4,

embed_dim: int = 96,

depths: Tuple[int, ...] = (2, 2, 6, 2),

num_heads: Tuple[int, ...] = (3, 6, 12, 24),

window_size: int = 7,

mlp_ratio: float = 4.0,

drop_rate: float = 0.0,

attn_drop_rate: float = 0.0,

drop_path_rate: float = 0.1,

num_classes: int = 1000, # Will be replaced with feature extraction

return_all_tokens: bool = False

):

"""

Initialize Swin Transformer feature extractor

Args:

image_size: Input image size

patch_size: Patch size for patch embedding

embed_dim: Embedding dimension

depths: Number of transformer blocks in each stage

num_heads: Number of attention heads in each stage

window_size: Window size for local attention

mlp_ratio: MLP hidden dim ratio

drop_rate: Dropout rate

attn_drop_rate: Attention dropout rate

drop_path_rate: Drop path rate

num_classes: Number of classes (not used, kept for compatibility)

return_all_tokens: Whether to return all feature tokens

"""

super().__init__()

# Use timm's SwinTransformer as backbone

self.swin = SwinTransformer(

img_size=image_size,

patch_size=patch_size,

embed_dim=embed_dim,

depths=depths,

num_heads=num_heads,

window_size=window_size,

mlp_ratio=mlp_ratio,

drop_rate=drop_rate,

attn_drop_rate=attn_drop_rate,

drop_path_rate=drop_path_rate,

num_classes=num_classes

)

self.return_all_tokens = return_all_tokens

self.feature_dim = embed_dim * (2 ** (len(depths) - 1)) # Final feature dimension

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

Extract features using Swin Transformer

Args:

x: Input tensor of shape (B, 3, H, W) or (B, 1, H, W)

Returns:

Feature tensor of shape (B, feature_dim) or (B, num_tokens, feature_dim)

"""

# Swin transformer expects 3-channel input, so repeat if necessary

if x.shape[1] == 1:

x = x.repeat(1, 3, 1, 1)

# Forward through swin transformer

# Remove classification head and return features

x = self.swin.patch_embed(x)

x = self.swin._pos_embed(x)

x = self.swin.patch_drop(x)

x = self.swin.layers(x)

x = self.swin.norm(x)

# Global average pooling

features = x.mean(dim=1) # (B, feature_dim)

return features

class DualBranchSwinTransformer(nn.Module):

"""

Dual-branch Swin Transformer for radar gait recognition

Processes spectrogram and CVD in parallel branches, each with

independent Swin Transformer feature extraction.

"""

def __init__(

self,

image_size: int = 224,

patch_size: int = 4,

embed_dim: int = 96,

depths: Tuple[int, ...] = (2, 2, 6, 2),

num_heads: Tuple[int, ...] = (3, 6, 12, 24),

window_size: int = 7,

mlp_ratio: float = 4.0,

drop_rate: float = 0.0,

attn_drop_rate: float = 0.0,

drop_path_rate: float = 0.1,

num_classes: int = 98

):

"""

Initialize dual-branch Swin Transformer

Args:

image_size: Input image size

patch_size: Patch size

embed_dim: Embedding dimension

depths: Depths for each stage

num_heads: Number of heads for each stage

window_size: Window size for local attention

mlp_ratio: MLP ratio

drop_rate: Dropout rate

attn_drop_rate: Attention dropout rate

drop_path_rate: Drop path rate

num_classes: Number of gait classes

"""

super().__init__()

# Spectrogram branch

self.spectrogram_branch = SwinTransformerExtractor(

image_size=image_size,

patch_size=patch_size,

embed_dim=embed_dim,

depths=depths,

num_heads=num_heads,

window_size=window_size,

mlp_ratio=mlp_ratio,

drop_rate=drop_rate,

attn_drop_rate=attn_drop_rate,

drop_path_rate=drop_path_rate,

num_classes=num_classes

)

# CVD branch

self.cvd_branch = SwinTransformerExtractor(

image_size=image_size,

patch_size=patch_size,

embed_dim=embed_dim,

depths=depths,

num_heads=num_heads,

window_size=window_size,

mlp_ratio=mlp_ratio,

drop_rate=drop_rate,

attn_drop_rate=attn_drop_rate,

drop_path_rate=drop_path_rate,

num_classes=num_classes

)

self.feature_dim = self.spectrogram_branch.feature_dim

def forward(

self,

spectrogram: torch.Tensor,

cvd: torch.Tensor

) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

"""

Forward pass through dual branches

Args:

spectrogram: Spectrogram input of shape (B, 1, H, W)

cvd: CVD input of shape (B, 1, H, W)

Returns:

Tuple of (spectrogram_features, cvd_features), each of shape (B, feature_dim)

"""

spec_features = self.spectrogram_branch(spectrogram)

cvd_features = self.cvd_branch(cvd)

return spec_features, cvd_features

if __name__ == "__main__":

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Create dual-branch model

model = DualBranchSwinTransformer(

image_size=224,

patch_size=4,

embed_dim=96,

depths=(2, 2, 6, 2),

num_heads=(3, 6, 12, 24),

window_size=7,

num_classes=98

).to(device)

# Test with dummy inputs

batch_size = 4

spec = torch.randn(batch_size, 1, 224, 224).to(device)

cvd = torch.randn(batch_size, 1, 224, 224).to(device)

spec_feat, cvd_feat = model(spec, cvd)

print(f"Spectrogram features shape: {spec_feat.shape}")

print(f"CVD features shape: {cvd_feat.shape}")

# Count parameters

total_params = sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters())

trainable_params = sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters() if p.requires_grad)

print(f"Total parameters: {total_params:,}")

print(f"Trainable parameters: {trainable_params:,}")# model.py

"""

Complete DST-A²F model combining dual-branch Swin Transformer

with Asymmetric Attention Fusion

"""

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from typing import Tuple, Optional

from swin_transformer import DualBranchSwinTransformer

from fusion import AsymmetricAttentionFusion, AdaptiveFusion

class DST_A2F(nn.Module):

"""

Dual-branch Swin Transformer with Asymmetric Attention Fusion

Complete architecture for radar gait recognition:

1. Dual-branch Swin Transformer extracts features from spectrogram and CVD

2. Asymmetric Attention Fusion combines features with prior knowledge

3. Classification head for gait identity prediction

"""

def __init__(

self,

image_size: int = 224,

patch_size: int = 4,

embed_dim: int = 96,

depths: Tuple[int, ...] = (2, 2, 6, 2),

num_heads: Tuple[int, ...] = (3, 6, 12, 24),

window_size: int = 7,

mlp_ratio: float = 4.0,

drop_rate: float = 0.0,

attn_drop_rate: float = 0.0,

drop_path_rate: float = 0.1,

num_classes: int = 98,

fusion_type: str = "asymmetric_attention",

feature_fusion_dim: Optional[int] = None

):

"""

Initialize DST-A²F model

Args:

image_size: Input image size

patch_size: Patch size

embed_dim: Embedding dimension

depths: Depths per stage

num_heads: Heads per stage

window_size: Window size

mlp_ratio: MLP ratio

drop_rate: Dropout rate

attn_drop_rate: Attention dropout rate

drop_path_rate: Drop path rate

num_classes: Number of identity classes

fusion_type: Type of fusion mechanism

feature_fusion_dim: Dimension for fusion (if None, use Swin output dim)

"""

super().__init__()

# Dual-branch Swin Transformer

self.backbone = DualBranchSwinTransformer(

image_size=image_size,

patch_size=patch_size,

embed_dim=embed_dim,

depths=depths,

num_heads=num_heads,

window_size=window_size,

mlp_ratio=mlp_ratio,

drop_rate=drop_rate,

attn_drop_rate=attn_drop_rate,

drop_path_rate=drop_path_rate,

num_classes=num_classes

)

feature_dim = self.backbone.feature_dim

fusion_dim = feature_fusion_dim if feature_fusion_dim is not None else feature_dim

# Feature projection if needed

if fusion_dim != feature_dim:

self.feature_projection = nn.Linear(feature_dim, fusion_dim)

else:

self.feature_projection = None

# Asymmetric Attention Fusion

if fusion_type == "asymmetric_attention":

self.fusion = AsymmetricAttentionFusion(fusion_dim)

else:

self.fusion = AdaptiveFusion(fusion_dim, fusion_type)

# Classification head

self.classifier = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(fusion_dim, fusion_dim // 2),

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Dropout(drop_rate),

nn.Linear(fusion_dim // 2, num_classes)

)

self.num_classes = num_classes

self.feature_dim = fusion_dim

def extract_features(

self,

spectrogram: torch.Tensor,

cvd: torch.Tensor

) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

"""

Extract and fuse features

Args:

spectrogram: Spectrogram input (B, 1, H, W)

cvd: CVD input (B, 1, H, W)

Returns:

Tuple of (spec_features, cvd_features, fused_features)

"""

# Extract features from both branches

spec_features, cvd_features = self.backbone(spectrogram, cvd)

# Project features if needed

if self.feature_projection is not None:

spec_features = self.feature_projection(spec_features)

cvd_features = self.feature_projection(cvd_features)

# Fuse features

if isinstance(self.fusion, AsymmetricAttentionFusion):

fused_features = self.fusion(spec_features, cvd_features)

else:

fused_features = self.fusion(spec_features, cvd_features)

return spec_features, cvd_features, fused_features

def forward(

self,

spectrogram: torch.Tensor,

cvd: torch.Tensor,

return_features: bool = False

) -> torch.Tensor | Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

"""

Forward pass

Args:

spectrogram: Spectrogram input (B, 1, H, W)

cvd: CVD input (B, 1, H, W)

return_features: Whether to return intermediate features

Returns:

Logits of shape (B, num_classes) or

Tuple of (logits, features) if return_features=True

"""

# Extract and fuse features

spec_features, cvd_features, fused_features = self.extract_features(

spectrogram, cvd

)

# Classification

logits = self.classifier(fused_features)

if return_features:

return logits, {

'spectrogram_features': spec_features,

'cvd_features': cvd_features,

'fused_features': fused_features

}

else:

return logits

# Test complete model

if __name__ == "__main__":

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Create model

model = DST_A2F(

image_size=224,

patch_size=4,

embed_dim=96,

depths=(2, 2, 6, 2),

num_heads=(3, 6, 12, 24),

window_size=7,

num_classes=98,

fusion_type="asymmetric_attention"

).to(device)

# Test forward pass

batch_size = 4

spec = torch.randn(batch_size, 1, 224, 224).to(device)

cvd = torch.randn(batch_size, 1, 224, 224).to(device)

# Without features

logits = model(spec, cvd)

print(f"Logits shape: {logits.shape}")

# With features

logits, features = model(spec, cvd, return_features=True)

print(f"Logits shape: {logits.shape}")

print(f"Spectrogram features shape: {features['spectrogram_features'].shape}")

print(f"CVD features shape: {features['cvd_features'].shape}")

print(f"Fused features shape: {features['fused_features'].shape}")

# Count parameters

total_params = sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters())

print(f"\nTotal parameters: {total_params:,}")Related posts, You May like to read

- 7 Shocking Truths About Knowledge Distillation: The Good, The Bad, and The Breakthrough (SAKD)

- MOSEv2: The Game-Changing Video Object Segmentation Dataset for Real-World AI Applications

- MedDINOv3: Revolutionizing Medical Image Segmentation with Adaptable Vision Foundation Models

- HiPerformer: A New Benchmark in Medical Image Segmentation with Modular Hierarchical Fusion

- How AI is Learning to Think Before it Segments: Understanding Seg-Zero’s Reasoning-Driven Image Analysis

- SegTrans: The Breakthrough Framework That Makes AI Segmentation Models Vulnerable to Transfer Attacks

- Universal Text-Driven Medical Image Segmentation: How MedCLIP-SAMv2 Revolutionizes Diagnostic AI

- Towards Trustworthy Breast Tumor Segmentation in Ultrasound Using AI Uncertainty

- DVIS++: The Game-Changing Decoupled Framework Revolutionizing Universal Video Segmentation